After 30 years of PlayStation, Sony is a very different company

Once a leader in consumer electronics, Sony is the PlayStation company now.

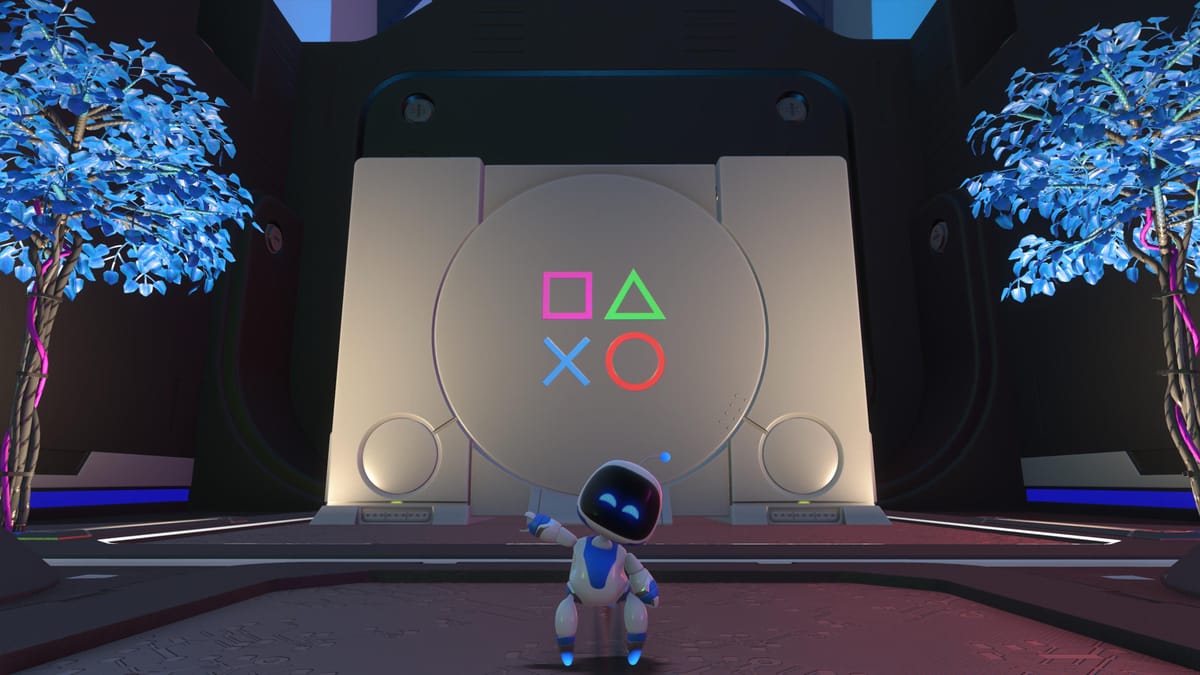

On December 3rd, 1994, Sony released the first PlayStation in Japan.

The original PlayStation revolutionized the industry, moving beyond child-friendly fare to target young adults with sophisticated games like Metal Gear Solid and Final Fantasy VII. The PlayStation 2 was an even bigger hit; it is, for now, the best-selling console of all time. Even during the company’s shakiest period, when hubris and a series of mis-steps led to a so-called “Icarus moment” with the PlayStation 3, it still outsold the rival Xbox 360. The PlayStation 4 was the dominant console of its era; the PlayStation 5 is matching the PS4's pace in sales.

And so the last three decades have seen a virtually unbroken string of success for the PlayStation. But while Sony’s fortunes in gaming haven’t changed over the years, Sony itself has undergone a dramatic shift. The Sony we know today is not the same company it was thirty years ago.

In 1994, calling Sony the pre-eminent consumer electronics brand of the time was, if anything, a huge understatement: Sony was one of the biggest brands in the world, period. It had a history of great products, sharp design and innovation. Among others, Sony co-developed the CD with Phillips; released the first OLED TV; even the giant Jumbotron screens at sporting events are a Sony creation.

That innovation also led the company down some odd paths, but that too was part of Sony’s charm. Aibo, the robot dog, is among many products emblematic of what tech writers dubbed “Weird Sony” — ideas that could be classed as anything between overly ambitious to deeply strange but which Sony built and sold anyway.

It could afford wild swings because the Sony of 1994 had so much going for it. It was the company that made the Walkman and Discman; the Trinitron and Handycam. Later that decade would come the Vaio line of PCs, Clié PDAs and Cyber-shot digital cameras. These were all iconic products that didn’t so much lead their categories as define them.

And this Sony did not welcome the PlayStation. Senior executives scoffed at making a game console. They saw games not as electronics, but as toys — and Sony didn’t make toys, it made high-end electronics. It was only after Nintendo publicly went back on an agreement to partner with Sony that, stung by the embarrassment, the company decided to make their own console. Still, other executives worried that the PlayStation would “destroy” the Sony brand.

Today, PlayStation is the Sony brand.

Take a look at Sony’s sales by segment for the year ended March 31, 1994, the last financial year before PlayStation's release. Video equipment, audio equipment and televisions made up the bulk of Sony’s sales; combined, those categories account for 57% of sales that year.

Contrast that with Sony’s most recent full-year financial report. Video equipment, audio equipment and televisions have been consolidated into a single category (ET&S) which makes up just 18% of sales. The biggest source of sales by far in the last year is gaming, with 32%.

Those signature Sony products I mentioned before — the Walkman, Trinitron, Vaio and Cyber-shot — most of them are either gone or irrelevant. Yes, Sony exists as a consumer electronics brand today: their Bravia TVs and noise-cancelling headphones are excellent. But they are outliers.

Sony’s demise as a consumer electronics brand is too big a story to tell in full here. Part of it is down to the march of technology; cassette players (Walkman) and bulky CRT TVs (Trinitron) have been obsolete for decades. Part of it is that some of those product categories (music player, digital camera) have been absorbed by the smartphone; there just isn’t a market for them anymore.

And part of it is that Sony is a company that made its name on high-quality hardware in an analog world where the quality of components made a big difference. It struggled to adapt to a digital-first world where software was important to consumers. The iPod didn’t win because it offered the best sound quality, it won because it was easy to use and automatically synced your music when you plugged it in. Meanwhile, Sony’s rival “MP3” player couldn’t actually play MP3s — it forced people to convert every song to a proprietary file type using finicky software.

Sony today is not a company that consumers interact with as much as they used to… at least, not knowingly. Because there actually is a Sony product that is more widely used by consumers than even the PlayStation; one that you’ve probably already used today without realizing. I’ll give you a hint: in the business segment chart, it’s under “Imaging & Sensing.”

It’s your smartphone’s camera. Or rather, the image sensor that powers it.

Sony supplies sensors to many major smartphones, the most notable of which is the iPhone. Apple is notoriously tight-lipped about exactly which companies contribute components for the iPhone, which makes it all the more significant that they’ve been vocal about their collaboration with Sony: Tim Cook tweeted that Apple has been "partnering with Sony for over a decade" on camera sensors in the iPhone.

It seems emblematic of the modern Sony that arguably their impactful product today is one that you’d never actually know came from Sony, buried inside a device that bears another company’s logo.

Which brings us back to a product that does bear the Sony logo, the last consumer flagship from a company that once dominated all areas of personal electronics: the PlayStation.

Before the pandemic, I had dinner with a senior PlayStation executive in Tokyo, who had a good-natured laugh at how much things had changed. In the beginning, Sony Computer Entertainment was sharing Sony Music’s spare office space far from the other divisions; now, his office is at the main corporate headquarters in Shinagawa. In 1994, senior leadership didn’t want to get into gaming; when we spoke, a former PlayStation executive was the CEO of the whole company.

Thirty years on, Sony has changed. It’s the PlayStation company now.