Elevator Action showed me what games could be

There's something deeply compelling about taking elements from daily life and building a game around them.

It’s probably no surprise that a kid from Hong Kong has a mild obsession with a game set in a high-rise building.

Elevator Action made a profound impact on young me because it was one of the few games of the time that took place in a recognizable version of the real world. As the name suggests, it built a game around a mundane part of everyday life: an elevator. In an era where most games were set in fantasy worlds, with gameplay revolving around arbitrary objects like the question blocks from Super Mario Bros., Elevator Action opened my mind to the idea that you could make games set in the real world.

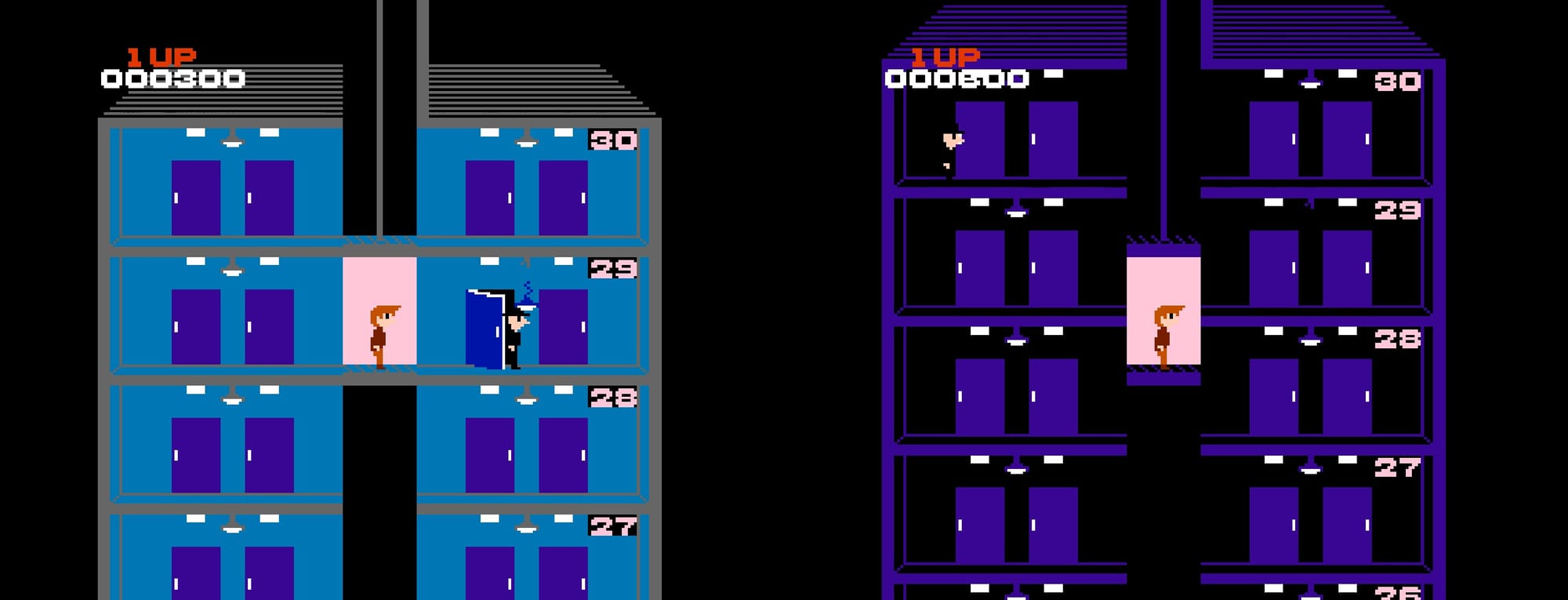

Originally released for the arcades in 1983 by Taito, Elevator Action is a heist game set in a tall building. You enter from the roof and have to proceed downwards through a series of elevators, stopping off to steal documents hidden in rooms marked with red doors. You start on the 30th floor and end at the basement, where your getaway car awaits. The longer you take to make it through the building, the more enemies appear, encouraging you to go through as quickly and efficiently as possible. (Marc Normandin’s excellent Retro XP newsletter has a more detailed description of the game.)

The setting may sound plain, but by the standards of that era, it was positively exotic. Back then games weren’t set in seemingly normal high-rise buildings. Even when games had real-world settings, it was such an abstract form of reality that it might as well have been fantasy.

That’s not to call out other games of that time. The basic capabilities of 1980s gaming hardware meant designers were very limited when it came to reproducing reality. Still, Elevator Action had several little touches that made the game feel quite real.

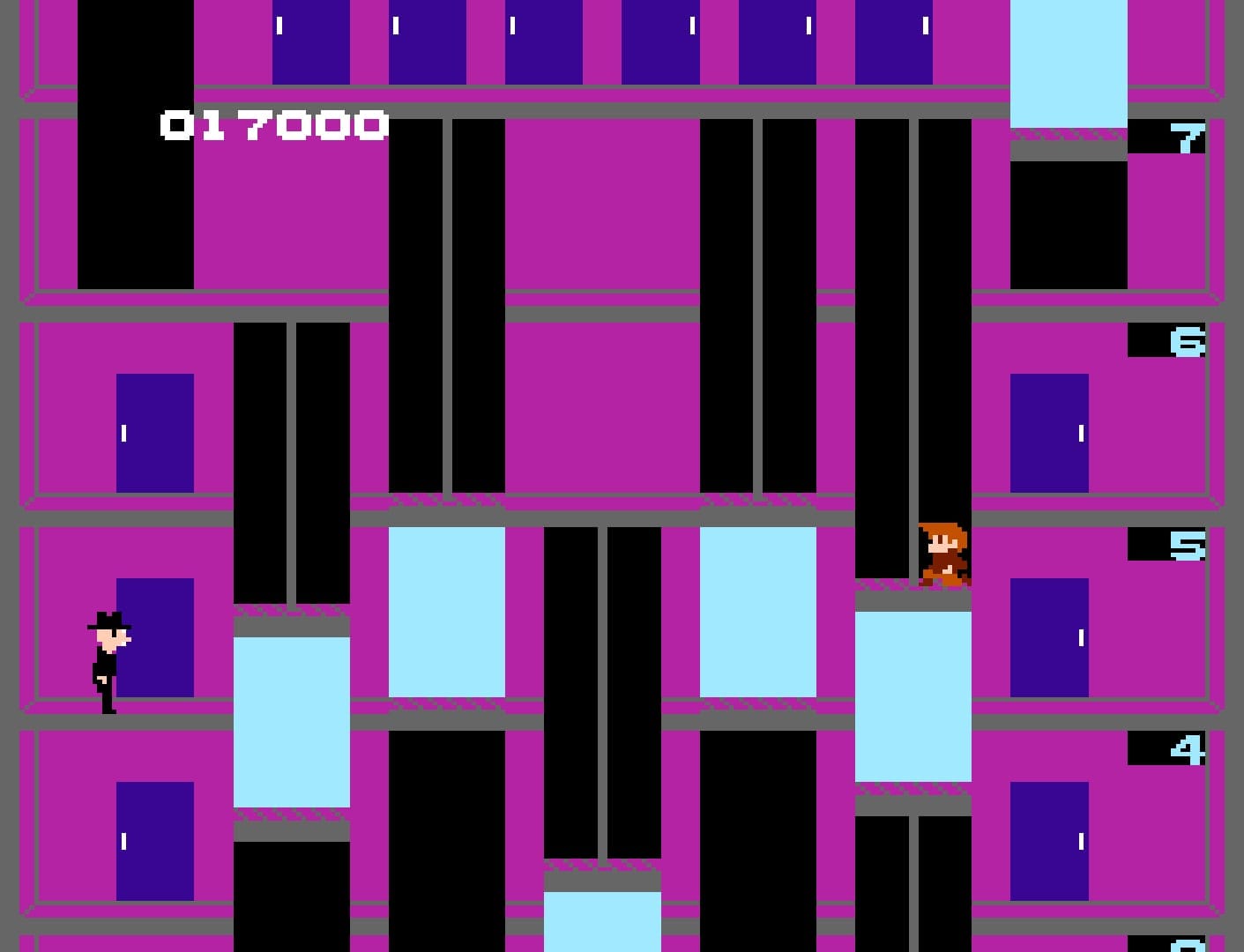

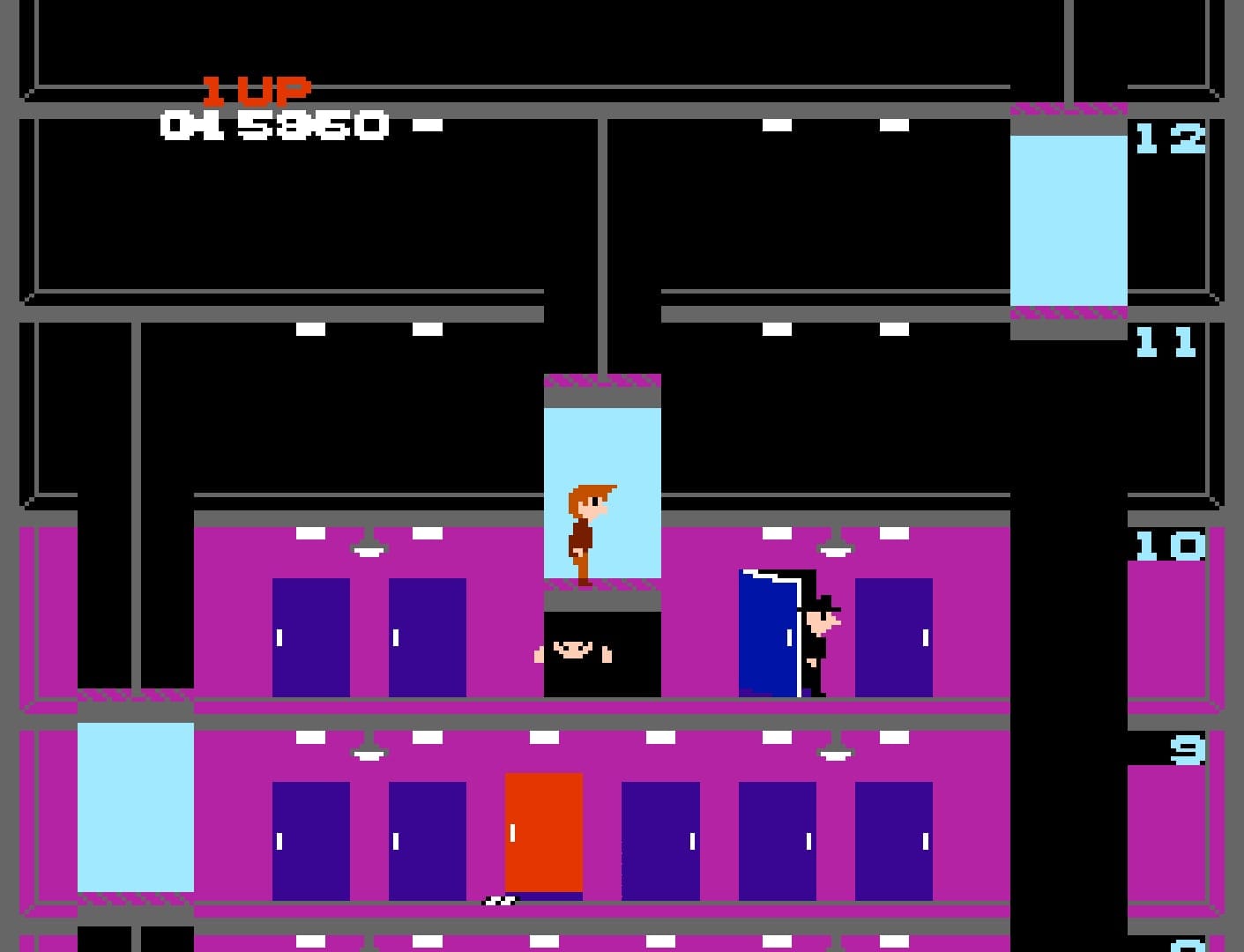

The enemies could use the same elevators you could — which meant, at times, they called away a lift that you were about to jump into. You could also shoot out the lights, which darkened floors and seemed to make you harder to see. It’s a small thing, but remember, this was 1983: interactivity like that was rare.

It also reflects Elevator Action’s playfulness. I don’t actually know how much you benefit from shooting out the lights — but I know it’s fun to nail that tricky shot and leave a floor in darkness. If you miss the lift, you can try to ride on the roof, like any good 80s action hero. And, most memorably of all, if you time things right, you might be able to catch an enemy under the lift… and you can squish them!

I don’t want to overplay the realism, because this is a simple arcade game from the early years of gaming. (I mean, I just said you could squish people under a lift like a cartoon.) But it’s interesting to see how real-world concepts influenced gameplay.

We all know the stress of being in a hurry and having to wait for the lift, and that feeling is core to Elevator Action. If you hop off on one floor to grab a file, the lift might be on another floor by the time you need it, forcing you to wait. And the longer you wait, the longer it takes, the more enemies appear in the building. When that lift returns, it may well be carrying a bad guy straight to your floor.

And if you’ve ever been in the lobby of a large building wondering which lift is the right one for your floor — that’s also a mechanic here. The high-rise you’re infiltrating is a little like a maze. Some lifts only go to some floors, so you need to figure out the right combination to get down to the basement.

There’s something I find so compelling about taking concepts from our daily life and twisting them to work as a game. And it feels distinct to me from gamification; where gamification is about grafting a gaming element (points, leaderboards, etc) into a real-world setting, this is about taking a real-world element and grafting it into a video game setting.

It might seem more imaginative to build a whole fantasy world from scratch, but in a weird way, I find that using a seemingly boring everyday object in a way that's entertaining is actually more creative.

It’s one of the reasons I was so taken with the first Harvest Moon, which took the look, feel and controls of The Legend of Zelda — and grafted it on to a farming game. There’s no combat, no dungeons, no princess to save, just crops to water. It’s why I love the Persona series, seeing how they take things like a social schedule or attending classes at school and making them gameplay elements.

And ultimately, I credit that fascination to Elevator Action. It showed me what games could be: not just based around arbitrary concepts in fantasy worlds, but turning the things you encounter in everyday life into a source of fun.