F-Zero GX is Sega doing what Nintendon’t

F-Zero X and F-Zero GX are reflections of what makes Nintendo and Sega great.

It was an idea so perfect and yet so unthinkable just the year before: in 2002, Nintendo announced that the latest installment of the F-Zero series would be developed by Sega.

It worked on so many levels. F-Zero is a series of futuristic, high-speed racing games; Sega is the king of thrilling arcade racers, the company behind an unparalleled string of hits from Out Run to Daytona USA. Nintendo, struggling to gain support for the GameCube, gets a big-name partner; Sega, needing to establish itself as a software power after discontinuing their own hardware, gets a powerful new ally. It was win-win.

But it was also a shocking twist, uniting two companies that had spent decades as bitter rivals. Nintendo versus Sega was the original console war, dividing a generation of gamers into picking between Mario or Sonic. One famous Sega ad from the era boasted that “Genesis does what Nintendon’t.” Executives fought not just in the press but even in US congressional hearings. Teaming up was inconceivable.

What made it so magical was that the partnership showcased the strengths of both companies. The resulting game, F-Zero GX, was released in 2003 for the GameCube to rave reviews. And for decades, that’s where it stayed: Nintendo never re-released it. It became one of my emulation white whales, something I’d always set up on my latest retro handheld.

Now, F-Zero GX is finally coming back. It’ll be part of a selection of GameCube games coming to Switch 2 as part of the Nintendo Classics program for subscribers of Nintendo Switch Online. At last, a new generation can check out this exhilarating game.

But to really appreciate F-Zero GX, you have to play F-Zero X first.

F-Zero X was developed by Nintendo and released on the N64 in 1998. As the previous game in the series, it provides the foundations for GX. More than that, it reflects the opposing, yet equally valid, viewpoints of Nintendo and Sega.

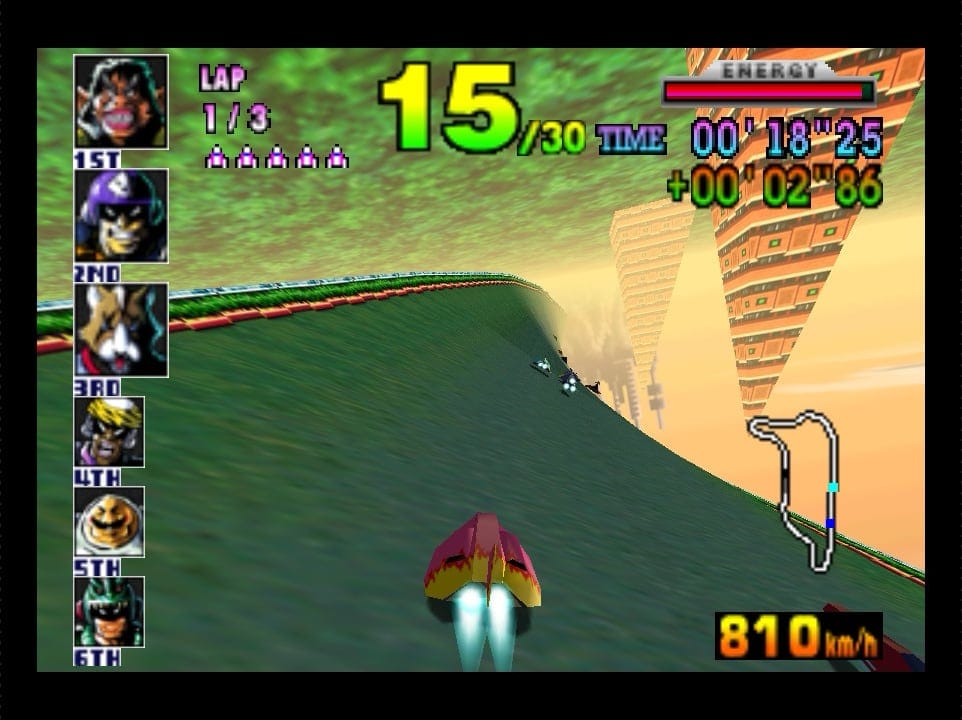

Your first impression of F-Zero X will likely be about how basic it looks. (You can try it for yourself: it’s available on the N64 Nintendo Classics app on the original Switch right now.) Even by the standards of early 3D gaming, F-Zero X is a bare experience: each racing craft looks crude and there’s little in the way of trackside decoration.

That’s because the priority on F-Zero X was to provide smooth, 60fps gameplay in a game where speeds can exceed 1500km/h. To achieve that with up to 30 racers on screen at once means stripping back detail, cutting extraneous visual flourishes until you get the austere look of F-Zero X.

Part of this is down to technical limitations, yes — the N64 can only handle so much. But I don’t think that entirely explains it. I think it reflects a degree of focus and purity that is quintessentially Nintendo.

F-Zero X’s tracks are often built around one singular gimmick: a big jump or a large section inside a pipe. When it chooses to deploy a graphical flourish, it does so with a purpose. One of the few trackside buildings you see appears next to the first track you play with a corkscrew — giving you a visual anchor to the surface to watch as the track twists.

Again, this is typical of Nintendo: taking a singular concept and building a level around it is a familiar formula for anyone who’s played a Mario game. And doing only what’s necessary to communicate the point, not adding extraneous detail that could obscure the message, is also a core Nintendo quality.

F-Zero GX, on the other hand, reflects Sega’s bombast.

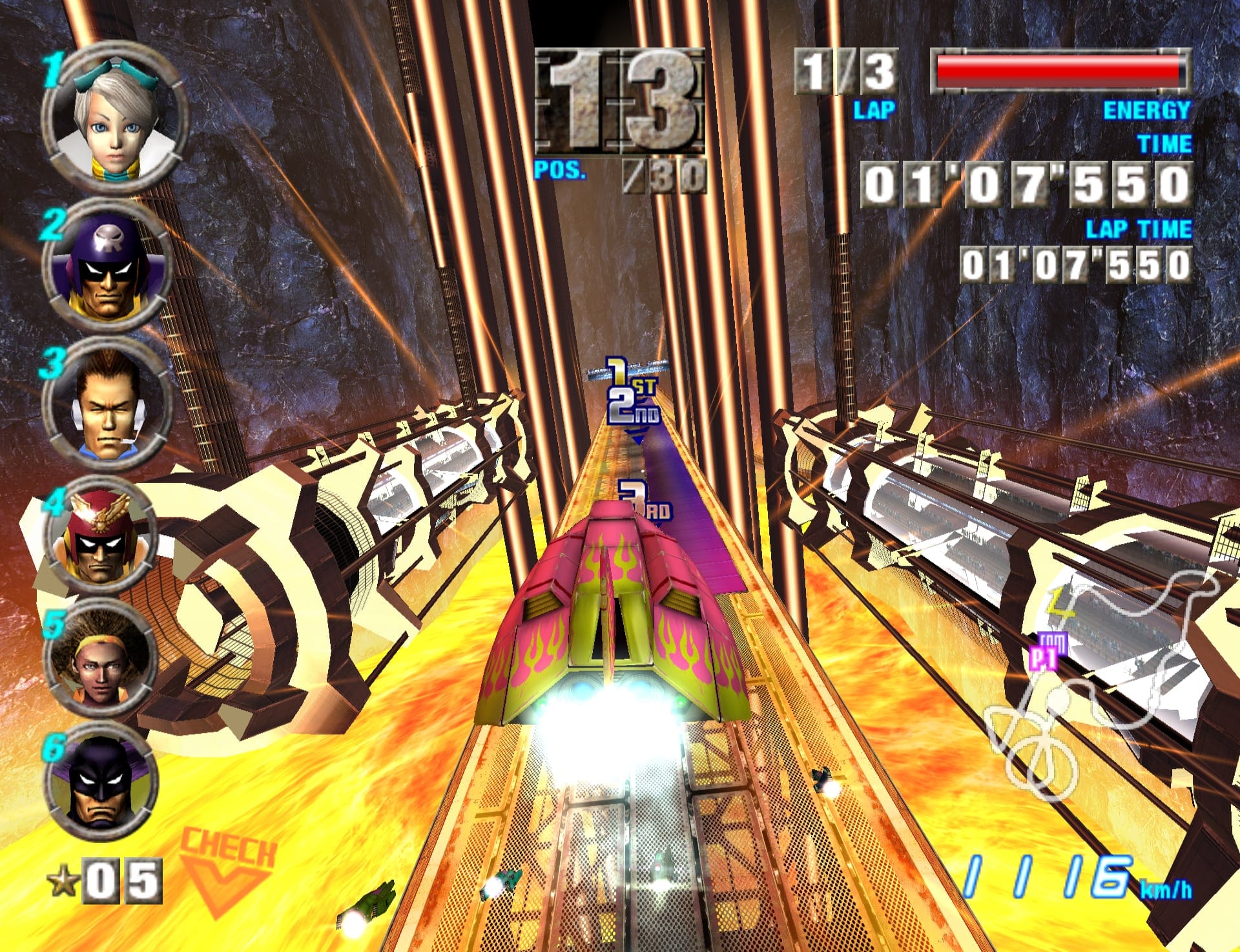

Where F-Zero X is austere, GX is an assault on your senses. Translucent billboards spin around the buildings crowding over the edge of the track. Flying vehicles whizz overhead. One jump takes you between two waterfalls. Pipes snake over a pool of magma. There’s even a track set amid a meteor shower above the Earth.

F-Zero X has the camera set further back, giving you a wider view of the plain track; this also means the track can obscure the plain backgrounds. In GX, the camera is pulled tight in on your craft, showcasing the detail and moving parts. In F-Zero X, activating boost makes your thruster glow green; in GX, boosting brings sparks of lightning dancing around your craft.

The tracks are still built around a theme, but have multiple gimmicks; one might have a jump and a section of steps, elements that would have been separated in F-Zero X. It’s exhilarating, but also slightly exhausting: I struggle to remember which track is which. And that’s the point, because GX is maximalist. It’s meant to thrill you by overwhelming your senses.

This is typical of Sega, because it reflects the company’s arcade heritage. Arcade games need to grab you from across the room, to show players something so exciting that they have to drop a coin in that machine. And one of the best ways to do that is to wow people with amazing sights: think of Sonic carved into the side of a mountain in Daytona USA, or Scud Race sending cars speeding through an underwater glass tunnel. Arcade games need to turn your head and sell you on the game in an instant. Sega brought that ethos to F-Zero.

Perhaps the best way to contrast the two is to look at their signature tracks, the ones that sell the concept of the games and embody their philosophies. F-Zero X’s signature track is Silence. On the map, it looks like a standard oval. But it twists on itself, rotating the track so that you never actually have to turn. Playing it the first time and realizing how the track loops in on itself for multiple laps without any actual corners is pretty mind-blowing.

F-Zero GX’s most memorable track is Green Plant: Intersection. It’s challenging and busy, with the first part taking place inside a twisty, dizzying pipe. Later in the lap, you get to a seemingly mundane bit: a wide bit of track with large columns in the middle that you have to dodge. It’s only when you go around again that you realize that they aren’t columns — it’s the pipe you were just inside of.

The pipe weaves in and out of the surface, almost as if it’s being loosely sewn on to the track. Heading back to that pipe for the second lap gives you the mind-bending thought that, as you sweep up and plunge downwards, you’re diving head-first into a surface you were just racing on.

It is an experience only Sega could have made — on a franchise that Nintendo owns. F-Zero GX feels like a fever dream, a partnership that was for years too farfetched to ever consider, but one blissfully made real.