Finding fun in constraints

Metaphor gave me what I wanted. So what’s wrong?

Note: There are no plot spoilers for Metaphor ReFantazio in this story.

Near the end of the brilliant PlayStation 5 game Metaphor: ReFantazio, a funny thing happened to me: I didn’t have anything left to do.

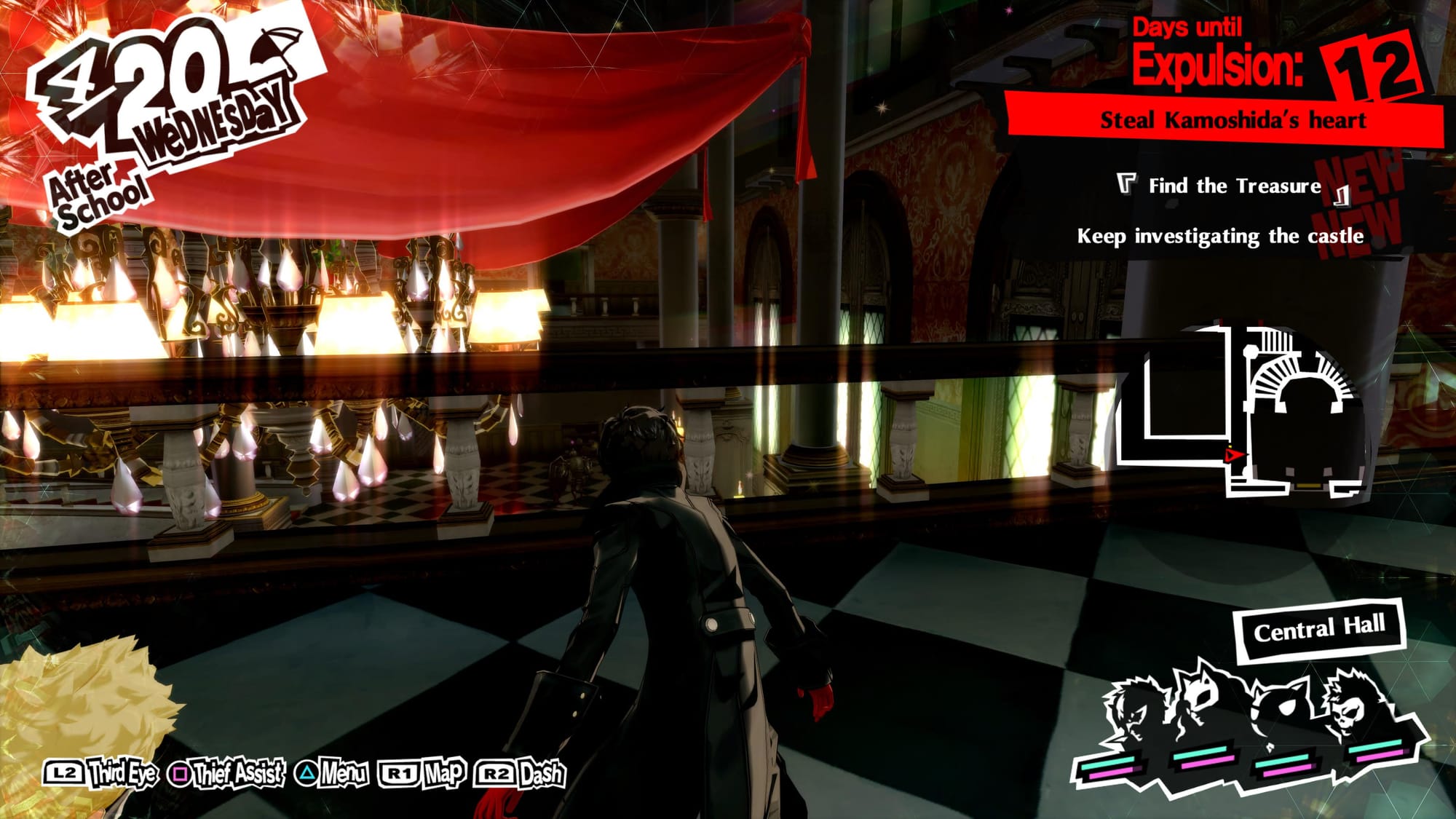

Metaphor is the latest game from the team behind the modern Persona games and adopts many of the same conventions. A series of Japanese turn-based RPGs known for bold and distinctive aesthetics, the Persona games run on a calendar. Each takes place over the course of several months, with each day divided into two segments. Taking on a mission or performing an activity will advance time to the next segment or next day.

There are deadlines to complete major missions by a certain date, but beyond that, you’re free to choose what to do with your time. Maybe it’s hanging out with a party member to improve their stats. Maybe it’s completing a side quest to get a helpful item. Maybe you want to head to a dungeon to battle and strengthen your team.

It is very possible — probable, even — that you’ll get to the end of a Persona game without actually doing all that you can do. There are too many quests to juggle, too many party members to look after, too many interlocking factors to consider. It’s too easy, especially in the beginning, to play the game inefficiently; to unknowingly invest in the “wrong” stats.

For instance, you might choose to spend time improving your Kindness without realizing that it’s smarter to invest in improving Knowledge earlier on, because it’ll trigger time-sensitive events and quests. Depending on how you play the game, you can lock yourself out of ever seeing certain events. I’ve finished a few Persona games, but I’ve never done everything I can do in them.

Metaphor keeps that system and all of those activities. But this time around, things are more streamlined. Your options are more clearly laid out, it’s easier to make progress and there’s more time to finish things.

This sounds like a good thing. And it should be a good thing! People complain about Persona’s calendar system all the time. It’s not uncommon to see players using a guide outlining exactly what they need to do on a day-by-day basis to see everything. It sounds awful, but I get it. I hate the idea of playing a game for over 100 hours knowing that I won’t be able to see all that it offers. (And these games are so long that I won’t replay them for years, if ever.)

That’s not true of Metaphor. I’m 80 hours in, with two weeks to go on the calendar, and I’ve done all that I can do. Instead of the doubts that plague me towards the end of a Persona game — have I done enough? — in Metaphor, I approach the end with a sense of calm.

So why do I feel dissatisfied?

You can argue that the limitations of Persona, and the lack of them in Metaphor, taps into something deeper, which is that constraints breed creativity. It’s a common enough idea outside of games and one that many of us have probably seen or experienced in our own lives: limitations can force you to see problems in a different way and to come up with creative solutions.

I do think that's part of it. But I think there's also something simpler at play: it's fun.

Persona forces you into a series of choices — hard choices, because you know that, say, choosing to spend time with Chihaya over Hifumi means you might not be able to complete Hifumi’s story. (I didn’t!) The choice can be agonizing, but ultimately, that's what games are about. Gaming is an interactive medium. Changing the outcome through your actions is why we play games. Facing a choice, thinking strategically about what matters and taking a gamble that you've picked the right choice – that's part of the fun of playing games.

Metaphor, while a superb game by virtually any other metric, lacks this tension. Recently, I’ve written about the benefits of offering players more choices, because the stories you make are always more powerful than the stories you’re told. Here though, you have more than enough time to do everything, so it doesn’t really matter what you choose to do. When you have the time to make every choice, there are no hard choices.

These aren’t the only games to demonstrate this principle. Think of the Halo series, where you can only carry two different guns. It forces players to make hard choices about how they want to play: do you want to keep a sniper rifle to pick enemies off at a distance, or a shotgun to get up close? It’d be easier to carry a gun for every occasion, but Halo forces you to come up with a plan.

Another example comes from the Dead Rising series. The Xbox 360 original tasked players with rescuing people across a zombie-infested mall. It had a notoriously limited save system; there were no checkpoints or auto-saves, only manual save points littered sparsely around the map. Players had to constantly weigh up the risks of pushing ahead without saving to perform a time-sensitive rescue — or making the long trek to a save point, abandoning that one survivor but securing their current progress.

The original Dead Rising’s save system was controversial at the time; years later, players still complain about it. But that save system is central to the game’s mechanics and tension. You’re supposed to agonize over whether to save your current haul of survivors or whether you can risk rescuing just one more person. In contrast, Dead Rising 3 bowed to player complaints and allowed you to save anywhere. It wasn’t received as well as the original; it lacked the tension and jeopardy that the series was known for. It just wasn't as fun.

As a veteran of Persona, if you’d told me in advance that I wouldn’t have to worry about getting everything done in Metaphor, I’d have been overjoyed. It’s exactly what I wanted.

But, it turns out, it's not what I needed.