GoldenEye doesn’t hold up, and that’s okay

The muted reception to GoldenEye 007’s return demonstrates how games are a unique mix of art and technology.

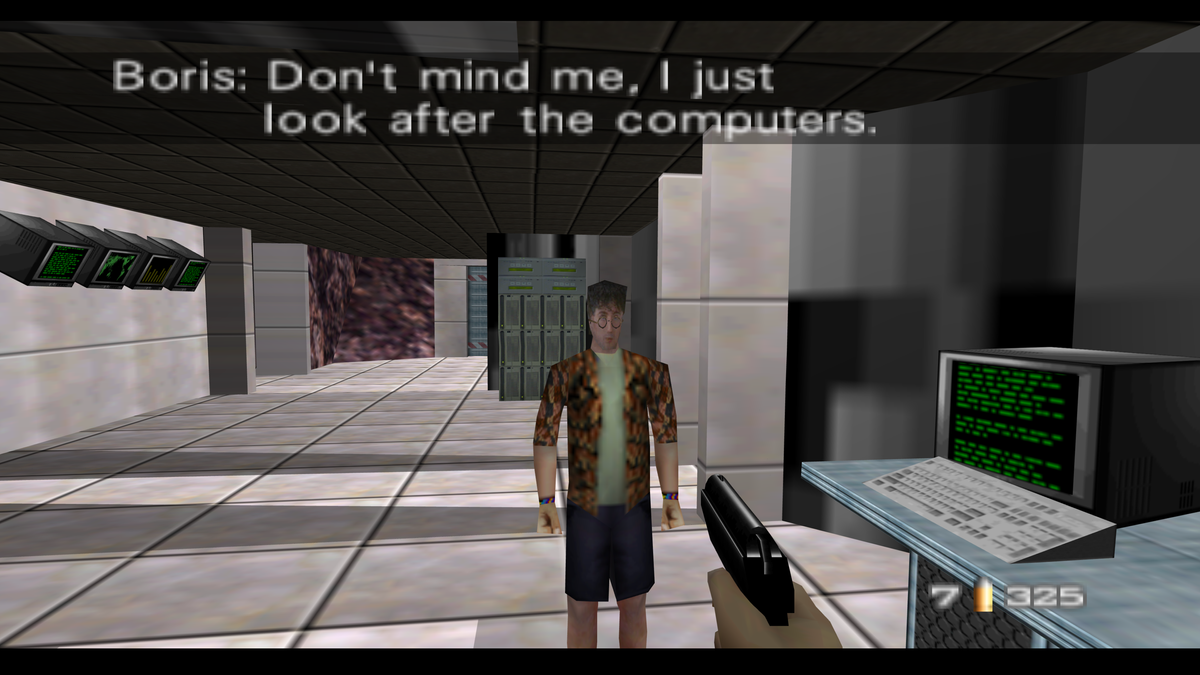

It’s taken over 25 years, but one of the greatest games of all time is finally available on a modern platform. GoldenEye 007 was released for the Nintendo 64 in 1997, and there it stubbornly remained: it wasn’t re-released on the Wii’s Virtual Console, an Xbox 360 remaster was seemingly cancelled at the last minute, and for years it was a notoriously tricky game to emulate. Even if you had a working N64 (and four unbroken controllers), hooking it up to a modern TV is a chore.

And so the game’s absence allowed its legend to grow: gamers of a certain age spinning tales of GoldenEye as a dorm room staple of the era, of banning Oddjob and Slappers Only matches, of cardboard cut-outs taped to TVs to hide your opponent’s screen, and of all-nighters consumed by one of the greatest multiplayer games of all time.

It’s no wonder that the announcement of GoldenEye’s return was met with excitement; it might seem more curious that the reception to its actual release last week was more muted. And the reason why was always going to be fairly clear: people hate the game’s controls.

The quarter-century since GoldenEye’s release has seen countless changes in gaming, among them the widespread popularity of first-person shooters and the standard dual-analogue control method. But GoldenEye was designed for the N64’s controller, which had a single analogue stick. And that design is woven deeply enough through the game that slapping a dual-analogue control method on top — as seen in the Xbox Series release and leaked Xbox 360 remaster — doesn’t cut it.

Quite simply, back in 1997, console gamers weren’t used to first-person shooters. (You could argue that gamers as a whole weren’t all that used to them either — Doom only arrived four years before GoldenEye, and Quake was released just a year earlier.) There was a real fear back then that the FPS controls we take for granted today would be too confusing for console gamers. In that sense, GoldenEye’s controls were quite clever: they basically allow a more casual gamer to move Bond entirely with the N64’s single analogue stick, relegating “advanced” functions like strafing (don’t laugh!) to the C-buttons — they’re there if you need them, but skippable if you’re overwhelmed.

To get around the lack of a second analogue stick for more precise aiming, holding down R freezes Bond in place and allows you to use the stick to aim instead of move. This is why, in turn, enemies in GoldenEye can feel slow and ponderous; it’s why they react to Bond by slowly kneeling, casually bringing their gun to their face, and then firing: they’re trying to give the player a fighting chance to do the same to them. If GoldenEye’s enemies ran and took cover like modern FPS enemies do, you’d struggle to follow them with your aiming cursor — and while you do, Bond is standing still, exposed to gunfire.

This control scheme, utterly perplexing today, was appropriate for the time: IGN’s review called it excellent, praising how it allowed Bond to move “naturally.” It’s notable too that contemporary games found no fault with it. Medal of Honor on the original PlayStation uses the same control concept as GoldenEye, despite supporting Sony’s dual-analogue Dual Shock.

In short, GoldenEye is very much a product of its time. But does that mean we’ve moved on from GoldenEye? Is it not, in fact, the classic we all remembered it to be?

The funny thing about video games is that they are a unique combination of art and technology. Sure, movies and music have components that rely on technology as well. But a child of today can still watch and appreciate Star Wars, 45 years after it was made; music written hundreds of years ago is still performed today.

Older games, though, are judged differently; they simply cannot be removed from the context of the technology of the time. As GoldenEye’s controls show, the technological limitations of 1997 have a material impact on how the game works and how it feels to play. What worked — spectacularly! — back then doesn’t work anymore.

And GoldenEye is hardly unique here: old arcade games like Space Invaders and Pac-Man used to hook kids for hours on end; I doubt any child of the 2020s would spend more than five minutes on them. The original OutRun remains one of my favorite games of all time, but driving games have moved on so far that I can’t imagine my son would find it terribly compelling.

But that doesn’t mean these games weren’t good. They have to be judged in the context of their time. And all of them — GoldenEye included — were stone-cold classics, groundbreaking games that paved the way for future titles to build on them and move the genre forward. Without GoldenEye to introduce so many console gamers to first-person shooters, would they be as popular today?

Games don’t have to last forever to be special, and we shouldn’t expect them to. They just have to make an impact. And that everyone is still talking about GoldenEye, 25 years later, tells you that this game was special — even if you can’t recognize that today.