I’m still using a Pokémon I caught over 20 years ago

Keeping old Pokémon is about more than holding on to memories.

On March 19, 2003, I chose Torchic as my first Pokémon in the just-released Game Boy Advance title Pokémon Ruby.

On January 4, 2024, that same Pokémon — now evolved into a Blaziken — helped me defeat the Champion of Pokémon Scarlet on Nintendo Switch.

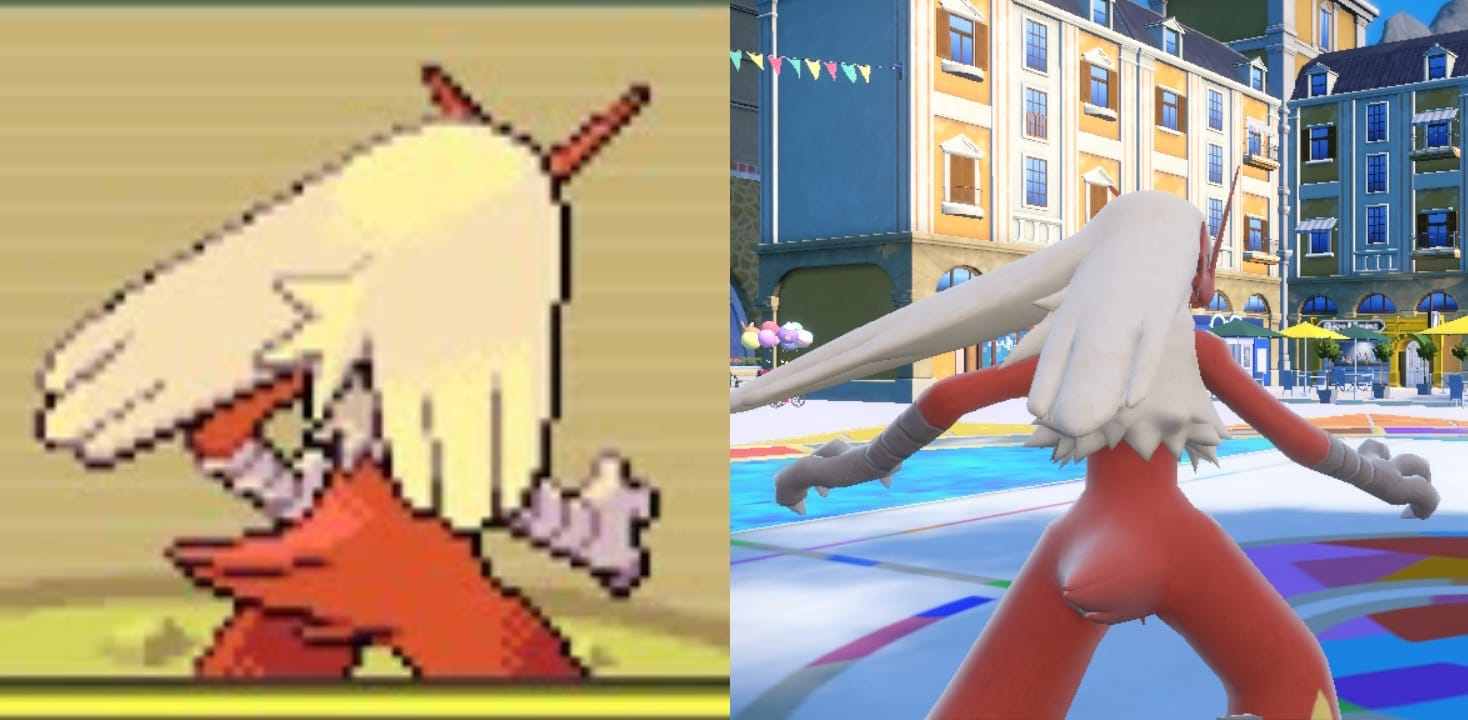

I don’t mean the same species of Pokémon. I mean it’s literally the same Pokémon. I saved the one I played with on the Game Boy Advance in 2003, transferred it from game to game, from Game Boy to DS to 3DS, until it ended up on the Switch. That same Pokémon, transformed from a blocky 2D sprite into a fully animated 3D model, helped me beat two Pokémon games 21 years apart.

To be clear, this isn’t a hack or a trick. It’s something encouraged by The Pokémon Company, and only made possible through a couple of services they run: Pokémon Bank and Pokemon Home. They’re paid services that store Pokémon in the cloud, allowing you to withdraw them when needed to use in various games.

I suppose you might be wondering why anyone would pay to do that. Most Pokémon aren’t scarce; each new game expects you to catch new ones, and new species are added all the time. So, why pay to keep old Pokémon?

One of the wonderful things about gaming is that, being both interactive and variable from player to player, everyone has their own special memories. It might be a tough boss fight, a close race with friends, or even a I-can’t-believe-that-worked moment where a desperate tactic succeeds. Ask any gamer you know, and they’ll remember certain triumphs or special moments, moments that will likely be quite different to your own.

That’s especially true with Pokémon. With so many to catch, everyone’s team is different; everyone focuses on training different Pokémon, or even training the same one a different way. The dozens of hours you spend getting through the game is going to build a bond with your party. Everyone’s got a favorite, or a Pokémon that you didn’t expect to like but ended up being critical anyway.

But the nature of the medium is that, with each new game, you always start with a blank slate: you have to catch and train a new team of Pokémon from scratch. After all, it wouldn’t be much of a challenge if you started a new game with your fully-trained team of champions from the last game. And you’d be less likely to break up a winning team to experience any new Pokémon.

And so it’s one of the quirks of the series that, for most players, they spend most of a Pokémon game building bonds and making memories — only to leave those same Pokémon behind when they move on to the next game.

That’s what happened to me. I built a team in Pokémon Ruby, trained them up to defeat the region’s Champion and entered the game’s Hall of Fame — and then, after 42 hours, I took the cartridge out of my Game Boy Advance and left it in a drawer. The same happened with the next Pokémon game… and the one after that… and the one after that.

In theory, I could have brought these Pokémon with me years ago. After Ruby, they allowed you to transfer your old Pokémon en masse from game to game… but only after you’d finished the newer game. This was great for competitive players, but for a casual player like me it was pointless: I never felt any desire to keep playing after a game was finished. On top of that, after Ruby there were a few Pokémon games that I never actually finished. So even if I wanted to bring Pokémon forward, the chain was broken: I couldn’t do it without finishing a bunch of old games on systems that I hadn’t touched in years.

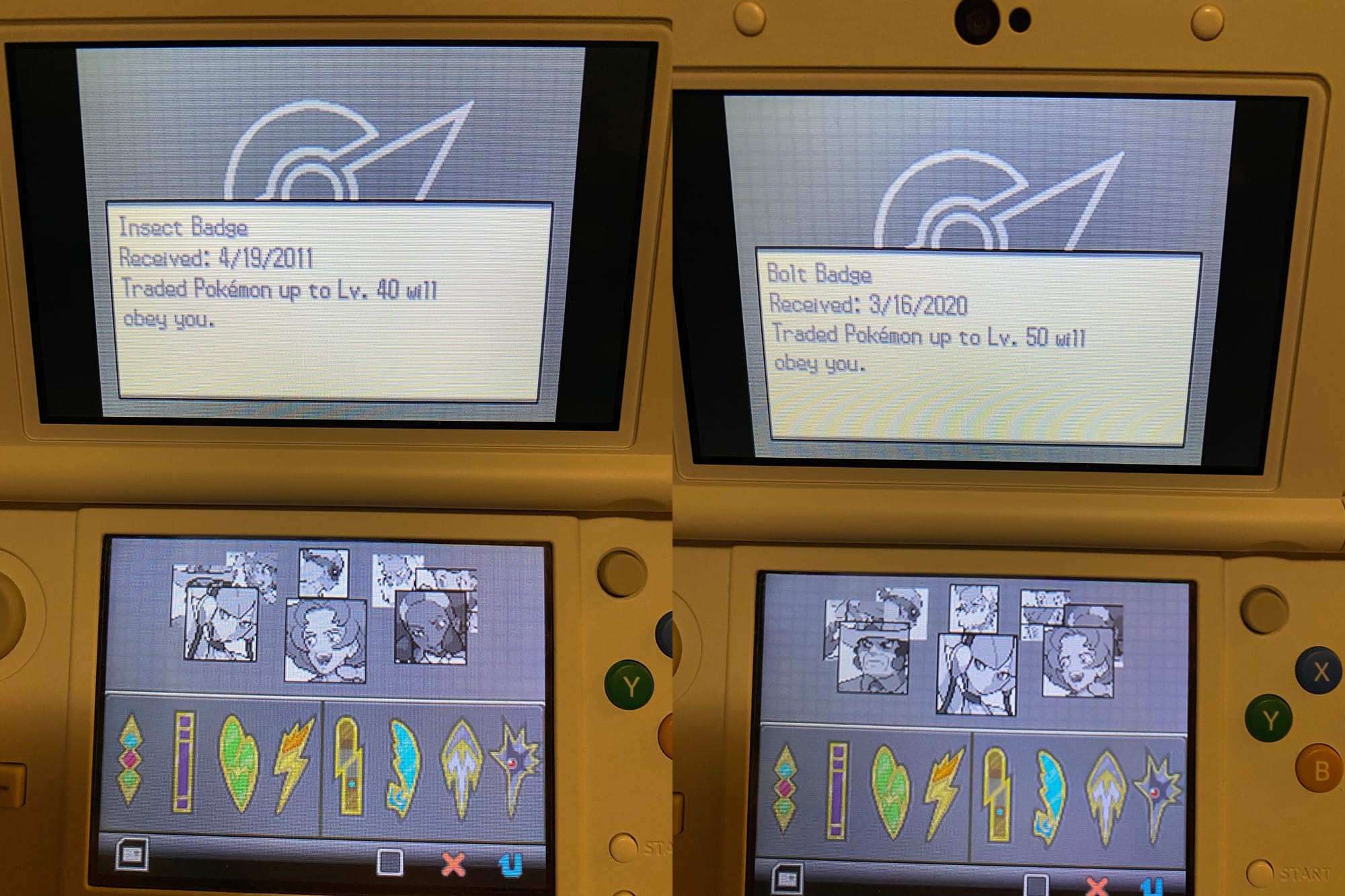

Then the pandemic happened. And, like so many other people in lockdown, I had a lot of time to devote to a project. You might have learned how to bake bread, but I used that time to play a ton of Pokémon.

It wasn’t hard — it just took a while. First, I had to dig up my old games and systems. Then I had to get them working again; thankfully, Amazon.co.jp had the chargers and link cables I needed. And then it was a matter of just sitting down and grinding through the games: I finished Pokémon HeartGold, Black and Sun within a few months, and then set about transferring Pokémon from each game to the next, taking hundreds of Pokémon caught in my decades as a player forward in time.

That Blaziken ended up touching seven Pokémon games on four generations of Nintendo console. And that history is recorded too. One fun little detail is that, if a Pokémon is used to beat the Champion of a certain game, it gets a little ribbon added to its profile to mark that achievement. And so it’s forever recorded that my Blaziken, caught half a lifetime ago, is a veteran that’s helped me beat Pokémon Ruby, Sun, Sword, Brilliant Diamond and now, Scarlet: five different Pokémon games.

Does it mean anything? Not especially; in pure function, there’s no real difference to me using my old Blaziken instead of a new one. But it’s pretty cool, right? It’s cool that I can still use these old Pokémon at all. And there is something special in knowing that a Pokémon that played a huge part in helping me finish a game two decades ago can still contribute to a game I’m playing today.

That’s one reason to keep old Pokémon. There’s another reason too; one that’s at once very silly, and yet oddly powerful.

When Pokémon Bank, the first cloud storage service, was announced in 2013 the president of The Pokémon Company shared a little story. Tsunekazu Ishihara said he’d spoken to a Japanese actress who asked for a service where she could safely store her Pokémon — so she could pass them down to her children and grandchildren. “She wanted something like Pokemon Bank because she wanted her kids and grandkids to remember that their grandma fought battles using Charizard,” said Ishihara.

This line was widely mocked. Hey, I laughed too! Pokémon aren’t heirlooms. There’s no limit to the number of, say, Pikachu that you can catch, so it’s hard to see them having any real value. They’re just little imaginary digital creatures. Who’d want to pass them down to their kids? They’re just Pokémon, right?

Well, now I have a son of my own. And my son loves Pokémon. It’s not a hypothetical anymore: there is a very real possibility that at some point in the future I will share my old Pokémon with him. I’ll pass down that Blaziken with its many Champion Ribbons; I’ll pass down that Latios I caught with my first throw of a Quick Ball; I’ll pass down that Ho-Oh that we stayed up way past his bedtime to catch together. As mad as it sounds, I’ll pass them down to him as if they are indeed heirlooms, and he’ll probably be thrilled to receive them.

He isn’t even five years old, so it’ll be a while until any potential grandchildren see my Pokémon. But Blaziken’s stayed with me for 21 years already. I won’t bet against Blaziken sticking around for a few more decades.