Majora’s Mask is a multiverse story

The Legend of Zelda's darkest entry used every tool to set an unsettling tone.

25 years ago, Nintendo released one of its boldest games. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask took one of the company’s best-known series and went in a surprising new direction, with a darker tone and more complex themes. A key element to the game’s unsettling nature is that it adopted a storytelling device that’s all too common now: it’s a multiverse tale.

To understand Majora’s Mask, we need to take a step back. Its predecessor, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, was hailed as the greatest game of all time almost as soon as it was released in November 1998. A sequel was not just inevitable, but necessary; the Nintendo 64 was floundering against Sony’s first PlayStation.

Majora’s Mask arrived just under 18 months later. It would have been understandable if, pressed for time, Nintendo played it safe and just did more of the same. I mean, it worked great the first time, right? The game’s working title, Zelda Gaiden — “Zelda side story” — didn’t imply any major changes. But Majora’s Mask was built around a whole new game mechanic.

The game begins with Link being transported away from Hyrule, setting for most of the Zelda series, to the land of Termina. The moon is set to crash into this world in 72 in-game hours (which translates into an hour in real time). You have to replay those three days over and over again, altering the flow of time and manipulating events to try and save Termina. By replaying those days, you become acutely aware of the routines of every one of the game’s characters, knowing exactly where they’ll be and who they’ll interact with.

This mechanic is totally new to the series and leads to some incredible gameplay scenarios. For instance, a shop tells you that they don’t have an important item because their delivery was robbed. You know when and where the robbery takes place. Do you stop it, allowing the shop to stock the item? Or do you let it happen, so a previous victim can track the thief back to his hideout?

But there’s a more powerful aspect to Majora’s time manipulation than gameplay, and that’s how it works as a storytelling device.

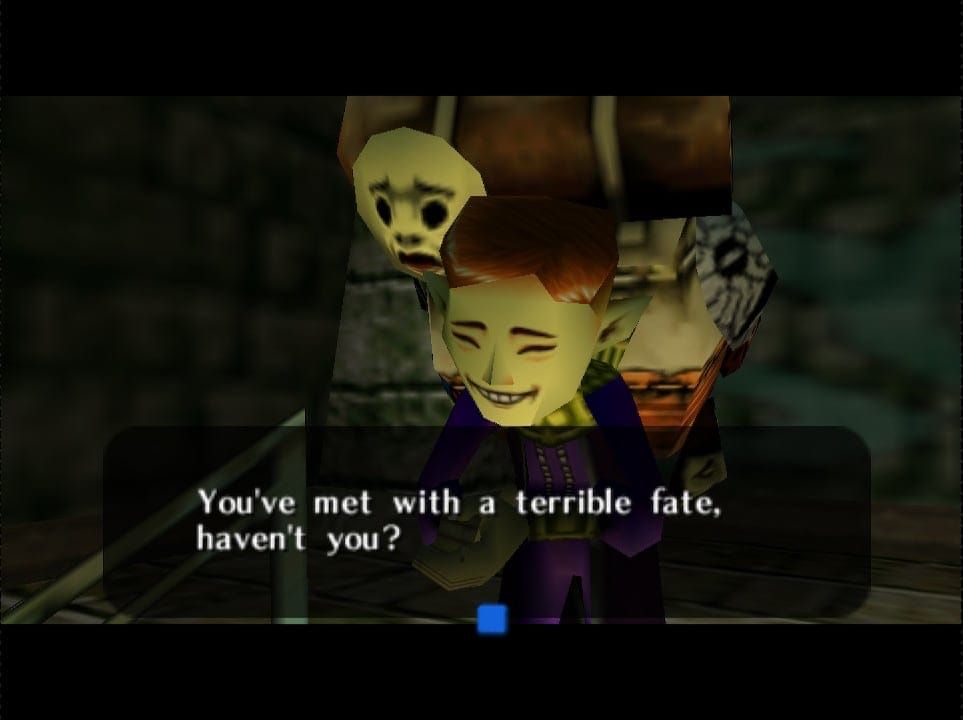

This is a world on the verge of the apocalypse, and very visibly so: the moon hangs in the sky, growing bigger with every passing minute. Being able to rewind time means that you’re able to follow every character as they slowly grapple with their fate. You can follow along as characters who were in denial slowly realize what’s happening; watch as some grow ever more panicked while others come to a grim acceptance. It’s powerful and haunting in a way that I’ve never felt in another game.

Adding to the unsettling atmosphere is an element that may be lost on modern players discovering the game on Nintendo Switch, a crucial bit of context that has been obscured over time: Majora’s Mask is filled with familiar faces from Ocarina of Time. Many of the character models from the previous game return for this one, but with new names and new backstories. But many of those have ties to their identities in Ocarina, making this a multiverse tale.

Okay, look, I’m almost sorry to bring the M word up. We’ve been so inundated with multiverse everything that we’ve already gone well past the backlash phase. I know you’re not just tired of hearing about multiverses, but you’re tired of saying that you’re tired of hearing about multiverses. I get it!

What’s interesting though is that this element was as much a technical decision as a creative one.

Ocarina of Time took three years to develop — a considerable length in those days, something that didn't help the charge that the N64 suffered from a lack of games compared to the rival PlayStation. The overwhelming critical acclaim Ocarina received was great, sure, but Nintendo needed more. They wanted to re-use the technology behind Ocarina to quickly release a sequel in about a year.

And so they made the decision to re-use, among other things, the character models they’d designed and built for Ocarina in this new game. They’d save time by having them look exactly the same, but with new names and identities they’d effectively be different characters.

Except that wasn’t quite true.

The characters weren’t entirely different, because they seemed to be linked to their doppelgängers from Ocarina. They were twisted versions of the characters you were familiar with. Some kept and doubled down on their old traits: a lady boasting about her dog in Ocarina now runs a dog racing track in Majora. Others became straight inversions, like Ocarina’s beggar becoming a banker in Majora.

The characters were cleverly crafted to play on your knowledge of the previous game, sometimes providing helpful context and sometimes using that context to mislead you. Take Gorman, for instance. Gorman is the manager of a traveling troupe. Most of the time in Majora’s Mask, he’s really grumpy and shouts at you to go away.

Gorman uses the same character model as Ingo from Ocarina of Time. Ingo was a farm hand who schemed and stole a ranch from his kindly (but dim) boss. Once he takes control, Ingo ditches his ragged work clothes for a colorful, overly-fancy outfit complete with an Elizabethan neck ruff, the same outfit Gorman wears in Majora’s Mask. When he assumes control of the ranch, Ingo is even more arrogant and rude. He even tries to swindle and imprison you.

So Gorman doesn’t just take the appearance of Ingo, he looks like the worst version of Ingo, and that matches how he treats you at first. But as you dive into his story, you realize that he’s different. He’s not shouting at you because he’s rude. He shouts at you because you’ve caught him at the worst time: Gorman is stressed and frustrated because his troupe’s gig at the year’s biggest event has been canceled at the last minute. You eventually discover that he’s a sensitive soul who misses his family and is trying to figure out how to do best by the people he leads. Gorman may look like Ingo and he may (at first) sound like Ingo, but he’s not Ingo.

This happens across the game. The evil twin boss witches from Ocarina are now friendly witches who run a magic shop. A tribe of desert thieves in Ocarina become a band of seaborne pirates in Majora. The postman in Majora, a character who conspicuously jogs across town checking mailboxes and making deliveries? That’s the Running Man from Ocarina.

In isolation, some of these may be nothing more than fun nods, but they add up. Twisting familiar characters like this adds to the feeling of uncertainty in Majora’s Mask. You might think it’s a source of comfort to see a familiar character again — but it’s the opposite, because their confounding behavior only adds to the confusion.

With the threat of the apocalypse hanging literally overhead in the shape of a rapidly falling moon, Majora’s Mask is a deeply unsettling game. The dark tone and heartbreaking stories from across the game give it a foreboding atmosphere never seen before (or since) in this most celebrated of series.

The game’s true triumph is how it generates that discomfort: not merely through the story or gameplay, but from the wider context around it. It was supposed to be a simple sequel, a hastily-built rerun of a winning formula that looks the same and plays the same. But in Majora’s Mask, everything is different — even the faces you think are the same.