Open worlds, closed levels

Star Wars Outlaws and the legacy of GTA3.

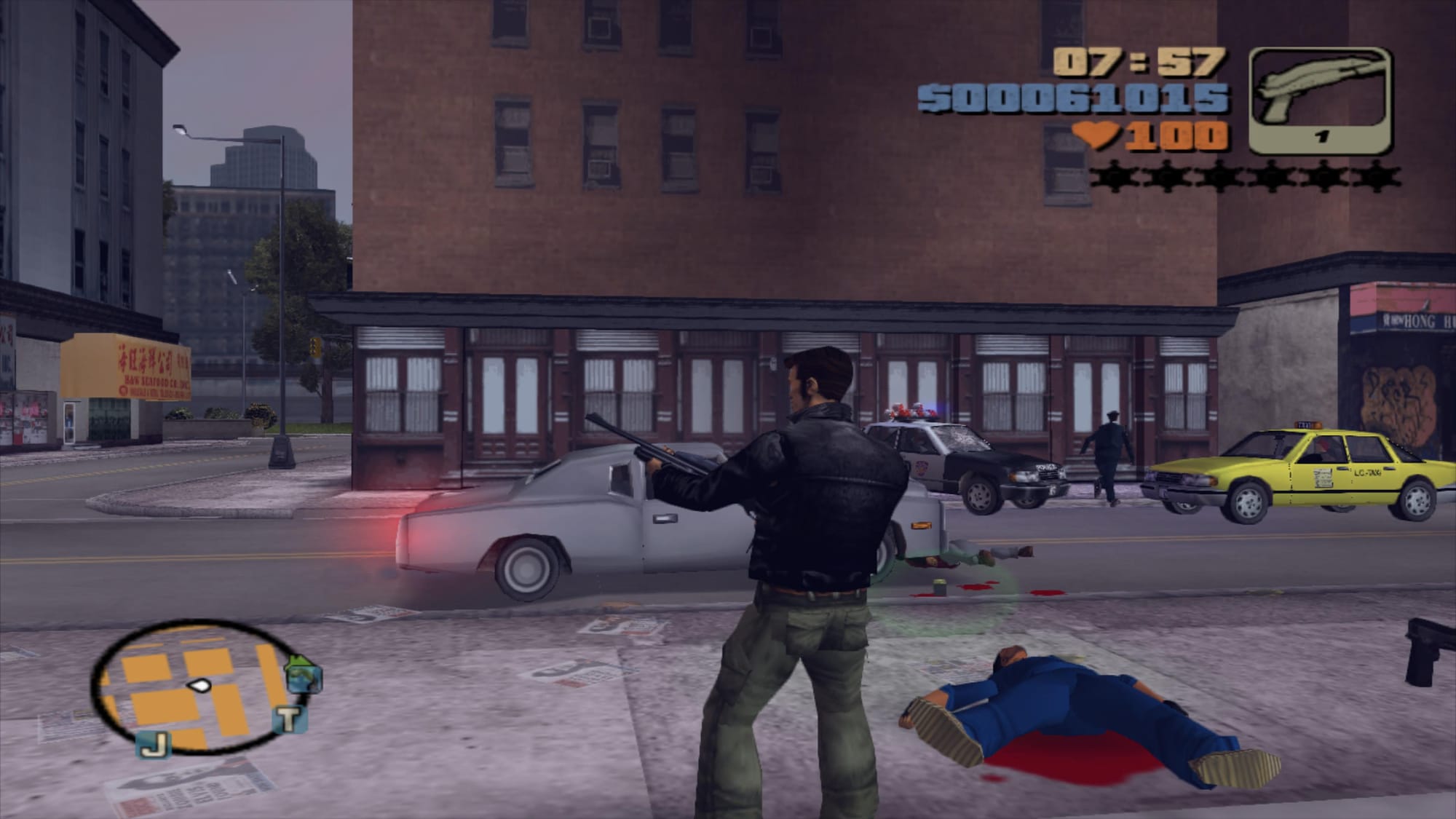

Grand Theft Auto III technically wasn't the first open world game, but it was the first truly influential one. GTA3 was such a success and so influential that, 23 years on from its release, it has come to define the genre.

Instead of a linear set of discrete levels — think World 1-1, 1-2 etc in Super Mario Bros. — GTA3 uses one large city as its sole “level”. Rather than being automatically shepherded from mission to mission, players can freely find and start missions and objectives across Liberty City. All around the player, computer-controlled pedestrians and cars move across the city independently, all with their own internal logic. If a computer-controlled car accidentally runs over a computer-controlled pedestrian, a computer-controlled ambulance will shortly arrive. This all happens without any input from the player; when the game launched, many people said they spent hours just sitting and watching, enthralled by the way Liberty City seemed to have a life of its own.

When players stopped gawking, they found that it wasn’t mere set dressing. Missions didn't take place in walled-off spaces, but in Liberty City itself, sharing the same space as all those random cars and people. If a mission involved a car chase, players have to weave through that traffic. Shoot at an enemy and pedestrians will flee in terror; start a fire and a fire engine will appear. If you’re lucky, that fire engine might park in a way to give you cover from gunfire — or, better yet, its overzealous arrival might flatten your enemy, unintentionally completing your mission for you. (This has happened to me… although the fire truck has also flattened me a fair few times too.)

The chaos and unpredictability of GTA3 was like nothing ever seen before. Gamers flooded forums with tales of car chases gone wrong, of crime bosses under their protection accidentally falling off cliffs, of evading one set of criminals by rounding a corner – only to end up in the crossfire of an unrelated gang war.

That freedom extended to missions themselves, which were often open enough to allow players to try different strategies. For example, one tasked players with killing a drug dealer. The dealer is protected by guards; as soon as you approach, he flees to a getaway car.

The simplest approach would be to go in guns blazing and hope you take him out before he escapes to the car, but given the number of guards, it’s risky. Most players end up continuing the pursuit in a stolen car, trying to run the dealer off the road. Others avoided the car chase entirely by obtaining a rare sniper rifle, picking him from a distance.

The best way of all was equal parts convoluted and clever. It involves first sneaking around the corner unseen to fit a bomb to his getaway car. Then, return to the front and approach as normal so the drug dealer sees you. He'll head straight for his car, and... boom. Mission complete!

That's one mission with (at least) four completely different ways to complete it. Players can exercise their creativity and apply all of the tools provided to them to come up with a solution.

But things would soon change. The success of GTA3 birthed a sequel the next year, Vice City, and another entry in 2004, San Andreas. An early mission in that game ends in a motorbike chase. Car chases are common in the GTA series, but this one felt different. Instead of a chaotic, semi-improvised chase through randomly generated traffic, this chase was scripted. You can’t try to cut a corner or take a shortcut to catch up; the bike follows a set path and always stays in front of the player. No matter what you do, it cannot be caught until the chase stops at a predetermined location.

On the face of it, this sounds like a clear downgrade. But there is a reason for it — and the very reason GTA3 was so enthralling is to blame.

You see, unpredictability can cut both ways. If you’ve got a car chase, but the traffic en route is randomly generated, it’s possible that one player gets a nearly empty road while another must navigate a near-impossible gauntlet of traffic jams and garbage trucks. Different players can get an entirely different experience; randomness dictates whether your version of the same mission is fun, frustrating or just boring.

By choosing to script the bike chase, San Andreas ensured that every player got the same experience with the same level of difficulty. Beyond that, designers were able to artificially engineer scenarios that couldn’t occur randomly. Chases in San Andreas are more cinematic than previous GTA games, with players jumping off bridges, crashing through billboards and even escaping from a big-rig truck on a concrete river bed… just like in Terminator 2. It trades spontaneity for spectacle: everyone gets the same experience, sure, but that experience is a guaranteed thrill ride.

This battle between open and scripted was on my mind while playing Star Wars Outlaws, the first open world game set in a galaxy far, far away. Despite releasing almost 23 years after GTA3, it too follows the same base structure. You’re a Han Solo-esque, well, outlaw; not a Jedi, not a Force user, just someone trying to get by in the grubby underworld that Star Wars does so well. Players are free to explore an open world that exists independently of them, with stormtroopers manning checkpoints, cantinas full of unsavory characters, and gang members on speeder bikes lying in wait outside cities. You can choose to work for Jabba the Hutt or against him; you can scour the badlands for treasure or hang out in a market listening for intel; you can focus on the main storyline or just go racing.

Your character, Kay Vess, isn’t a one-person army, so you have a wide variety of non-combat options to help you navigate tricky situations, like a little alien pet that can distract guards. One of my favorite moves is definitely out of the Han Solo playbook: if you’re spotted, instead of immediately getting caught, you have a few seconds to jump out of cover with your hands up, babble some improvised nonsense to confuse the guard — and then use that confusion to race out of there. It’s a delightfully on-brand move for Star Wars.

The problem is that those tools aren’t always exploited to their fullest in missions. You may have a set of tools and abilities far surpassing anything in GTA3, but the missions follow the scripted, cinematic philosophy of San Andreas.

One early mission tasks you with infiltrating an Imperial base. This base sits high atop a bluff, with a road leading to the only entry gate. My instinct was to recon the whole bluff, scouring each side for potential entrances or weak points. But I shouldn’t have bothered: if you head for the front door, you’ll notice that just off to the side is a suspicious-looking path, conveniently ignored by nearby stormtroopers, leading to a set of climbable walls. The designers couldn’t have made it more obvious: the world may be open, but this is the one and only path for you to take in this mission.

Another mission has you trying to traverse the inside of a different Imperial facility. You’re perched on a ledge on one side of a large, open room and you need to get to a control panel on the far side. The room has the sort of layout that, in another game, would suggest multiple options for getting across, depending on your chosen style of play. Instead, there is a very specific way across this room, involving you using your abilities in a set order: hack that, jump there, cover here, swing over that, climb that wall… you get the idea. The room is vast, but there is only one prescribed route across it. Each step is effectively a scripted one, forcing you to use a specific move at a specific time.

This is a common issue with Outlaws. The game’s main challenge in missions is not, say, to avoid stormtroopers; it’s to divine the intent of the designers. It also stands in stark opposition to the rest of the game. Outside of missions, the world is vast and open, with big landmarks and small details carefully laid out to pique your curiosity and pull you in different directions. It’s a world that rewards curiosity and experimentation — “hey, what if I use this here…?” But the missions don’t follow that philosophy. There’s one path for you to follow; your job is to spot the breadcrumbs.

What makes this approach especially frustrating is that it doesn’t feel true to your character and it doesn’t feel true to the universe it’s set in. Han Solo is a master of improvisation, and Kay Vess is (intentionally) cut from the same cloth. Instead of allowing us to improvise as those characters would, we’re forced to play through someone else’s interpretation of what they would do. You’re not thinking about the tools at your disposal to find your own solution; you’re looking for their solution.

It feels archaic. The heavy-handed nature of San Andreas may have made sense in 2004, but that was twenty years ago. Games have evolved and technology has improved; what seemed impossible before is possible now.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the current standard-bearer for open world games. Where GTA3 was once the model, today the most influential open world title is The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. It pushes the concept further by making the world even less structured, even more open, and fully interactive. One of those breakthroughs was the ability to climb any wall, a rare ability in games. Designers often place strict limits on where players can go, allowing for a more controlled experience. But Breath of the Wild lets you climb anywhere, vastly opening up the possibilities for exploration and giving players a large degree of freedom. Outlaws, in contrast, limits climbing to very specific walls marked out with gaudy yellow paint — a common approach in the past, but one that feels dated after Breath of the Wild.

The sequel, Tears of the Kingdom, goes even further with a mechanic that allows you to build things to solve puzzles or traverse the world. The beauty of it is that, if you hand players a stack of building materials, each one will approach the problem in a slightly different way. If you need to cross a river, do you build a bridge or a boat?

This matters because at the end of the day, your solution will always be more memorable to you, because the stories you make are more powerful than the stories you’re told. Whether it’s a perplexing puzzle in Tears of the Kingdom or a mission that’s gone wildly off the rails in GTA3, you may not have done things in the best way — but you’ve done it your way, and you’ll remember that.

Even Outlaws demonstrates this. That mission inside the Imperial facility inevitably goes bad, and the Empire starts chasing you. I jumped on my speeder bike and shot out of there, narrowly avoiding stormtroopers at the gate. The nearest path to clearing my bounty was to the right, near a stormtrooper roadblock, but I thought I’d go left, lose them in the tall grass of the savannah and double back later. A few seconds later, without a stormtrooper in sight, I thought I was safe… and then I heard TIE Fighters screaming overhead, looking for me. I spent a good few minutes trying to evade them before racing towards the planet’s major city (“they’d be crazy to follow us…”). Then, I crashed through an Imperial roadblock, dodged two stormtroopers by jumping off a ledge, and reached a crooked Imperial officer just in time to pay a bribe and call off the chase.

I should have just gone to the right. That’s what it felt like the game wanted me to do. But I made my own choice — a bad one, probably — and had to rescue an ever-escalating situation. It felt, well, like Star Wars; it hit the right spots in so many places for an old Star Wars fan. It was easily the highlight of the game so far for me, and it came out of a bad decision crashing into a series of unintended consequences.

24 years later, the design championed by GTA3 is as compelling as ever.