The PlayStation Portable felt like the future

Twenty years ago, Sony tried to redefine portable entertainment with the PSP. What happened?

It’s after midnight. The last train is long gone and this station in the far corner of Hong Kong is almost empty.

Exactly twenty years ago I stood there, fingering a wad of far too much cash in my pocket, eyeing the few figures loitering around the station and wondering which of them is about to take my money.

Someone walks up to me. It’s him. There’s some smalltalk. It’s all very polite, but we’re both anxious to get this over with. He opens his bag to show me the goods; I nod and hand over the cash. He gives me the package and we part. (But not before another bout of smalltalk.)

I am tempted, so tempted, to open it up and take a look. But not here, not now; it’s not wise to let anyone see what I’ve got.

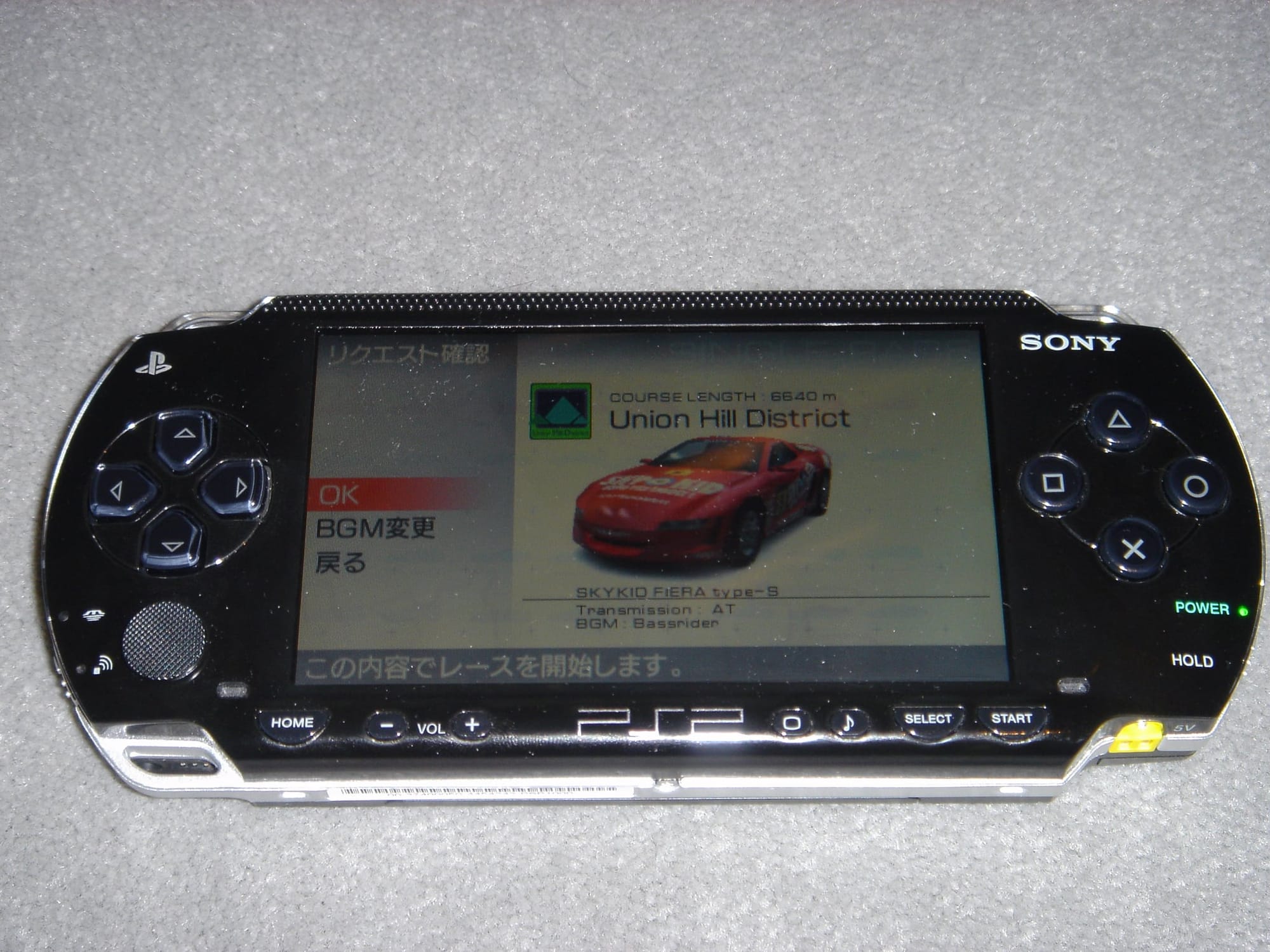

It’s not until I get home that I finally unwrap my prize: the PlayStation Portable, one of the first units to arrive in Hong Kong, a full day before anyone in Japan was able to buy one. I actually got it so early that I didn’t have any games — not that I cared. I was just happy to have it.

Nothing ever felt more like the future than the PlayStation Portable. I’ve played with a lot of fancy gadgets in my life, and there aren’t too many times I remember just staring at a device in wonder as I did the first time I held the PSP.

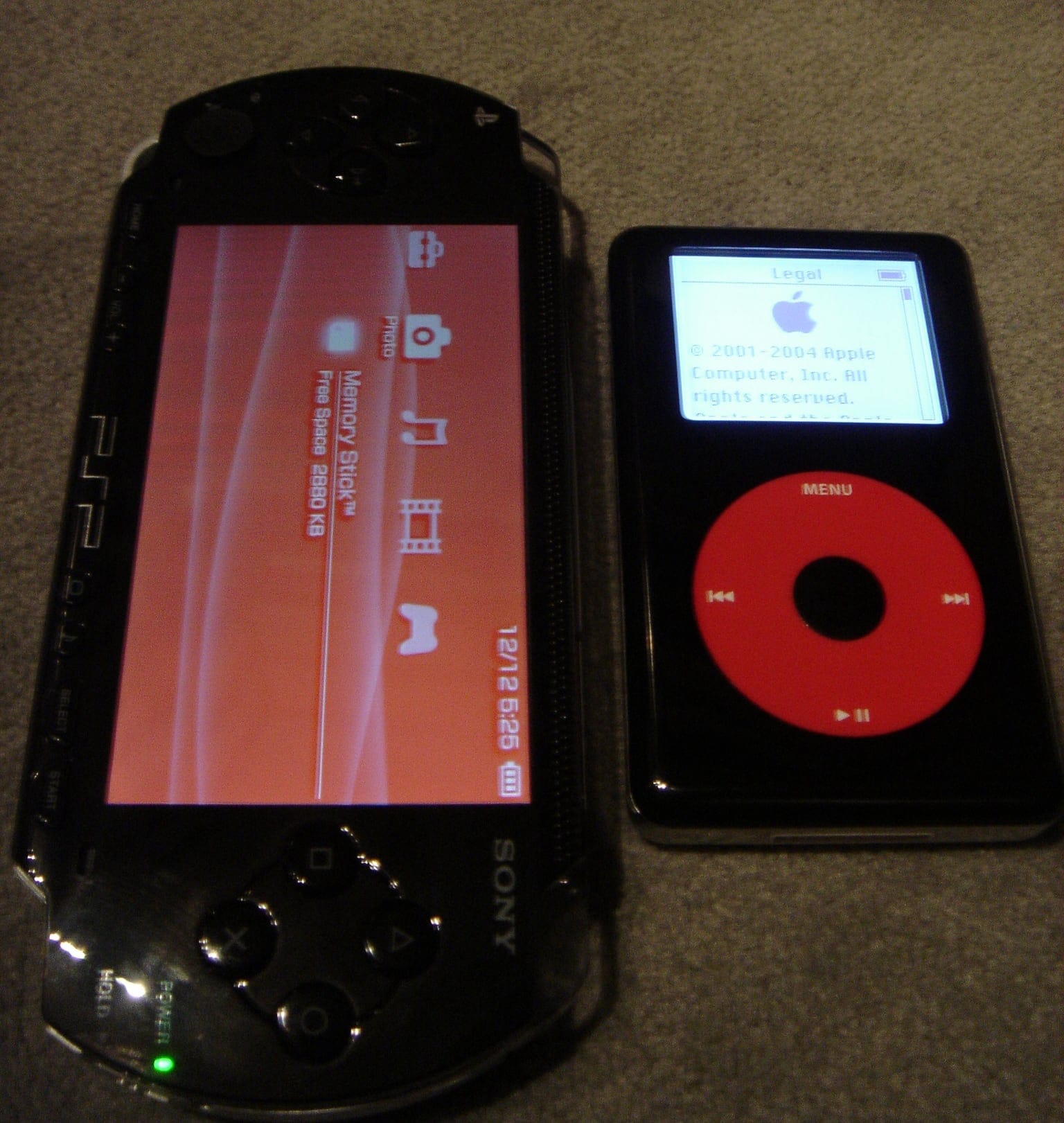

The first thing you notice is the massive screen. It’s big even by today’s standards; at the time, it was barely believable. For context, the PSP’s screen was the size of an entire iPod. It also had a glossy black finish, clear buttons that looked like glass, and a special disc drive on the back. Oh, and on the inside, it was comfortably the most powerful portable console ever made, with games promising visuals almost on a par with the PlayStation 2. It felt impossible that this combination of features could exist in any portable product, yet alone one as small and light as this.

More important than the hardware specs is what the PSP represented: it was the empire striking back.

In 2004, Sony was still the biggest name in consumer electronics, but it was facing an unexpected threat. iPod sales were booming; it was being hailed as the successor to the Walkman, making the iPod the 21st century’s must-have personal music player. More surprising was that it came from Apple, which until that point was primarily a computer company. It wasn’t uncommon to hear people wonder why Apple made the iPod when it felt like it should have come from Sony.

And so the PSP wasn’t supposed to compete with the iPod per se — it was supposed to surpass it. It had a slot for a Memory Stick to store songs on, so it could play music like the iPod. But it was also a PlayStation, so it could play games. And Sony wanted to position the PSP’s disc format, UMD, as a new standard for other devices to adopt — basically, the portable equivalent to DVDs — so they released movies, concerts and TV shows on UMD. (You could also watch TV shows and movies acquired from, ah, less-than-legal sources by transferring them to the Memory Stick.)

Sony’s vision, then, was for the PSP to be an all-encompassing personal portable entertainment device; taking the idea of the iPod, but going far beyond portable music by supporting movies and games as well. Ambitious? Sure. But honestly, at the time, it was hard to see the flaw in it.

Sony’s first 10 years in gaming had gone perfectly: the original PlayStation was the best-selling console of all time and the PlayStation 2 was on course to shatter that sales mark. Taking that expertise and combining it with the decades of experience Sony had in building innovative, world-beating personal electronics like the Walkman, Discman and Handycam seemed a perfect combination on paper; it was an even more convincing proposition when holding the PSP in your hands.

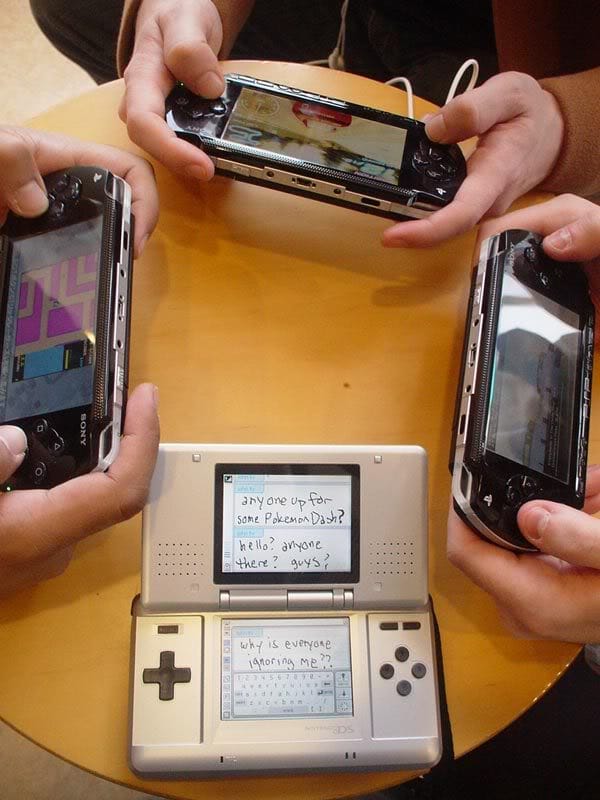

What helped was that, as Sony seemed to be making all the right moves, it looked like Nintendo was making all the wrong ones.

Three weeks before the PSP’s debut, Nintendo released their own next-generation handheld, the DS. Where the PSP’s strengths were more immediately apparent, it wasn’t as easy for gamers to grasp why the DS’s dual screens or touchscreen was something they needed. Nintendo didn’t help either, calling it a “mystery” product in their initial unveiling. They also referred to it as a “third pillar” alongside the GameCube and Game Boy Advance, which made it feel less like the successor to the Game Boy and more of a weird little experiment.

Some of you might know what happened in the end: the DS outsold the PSP comfortably. It was the vanguard of a new strategy for Nintendo, one it’d embrace with the Wii, of seeking the widest possible audience with games that attracted non-gamers like Nintendogs and Brain Age.

But that success came much later. I’d wager that most people’s fond memories of the DS are actually of the DS Lite, the sleek, Apple-esque redesign.

The original DS that we got at launch, the one that launched right before the PSP, was an awful piece of hardware. It was bulky and plasticky, with odd angles that made it uncomfortable to hold. It launched with an ugly version of Super Mario 64 that was controlled in the most bizarre way: you attached a strap to your thumb with a little plastic nub on it, and you pressed that nub on to the touchscreen to move Mario around. It was deeply strange and unintuitive.

One of the reasons the original PlayStation was so successful was that it targeted older teenagers and young adults that felt alienated by Nintendo. The PSP had that same feel: this wasn’t a toy for children like a Game Boy, this was a sophisticated device for adults (or for younger people who wanted to feel like adults). It was hard not to see history repeating itself when you looked at their two new portables.

That didn’t happen. But why?

Firstly, I think it’s important to note that the PSP didn’t exactly fail. Yes, it was outsold by the DS, but it did sell over 82 million units; that’s more than the 3DS and roughly on par with the Game Boy Advance.

It did not, however, become the future of digital entertainment. And part of that is down to the fact that it wasn’t really digital entertainment at all, because the PSP was effectively reliant on physical media.

Whether you bought songs from the iTunes Music Store, ripped them from CDs or downloaded MP3s illegally, music on the iPod was all digital and all automatically synced with your computer via iTunes. That was the iPod’s true revolution: moving from the limits of juggling physical media to giving people access to thousands of songs from a variety of sources at the same time. It was virtually effortless; far easier than dealing with Sony’s finicky PSP media software or managing the limited storage space of a Memory Stick.

For all intents and purposes, if you wanted a movie on your PSP, you had to buy it on UMD… if that movie was even released on UMD to begin with. Remember how I said Sony hoped that UMD would become a new standard, the portable equivalent to the DVD? Yeah, that didn’t happen. The only device to ever use UMDs was the PSP, so relatively few movies were released for it. (Sony would also release a PSP that didn’t play UMDs.)

And ultimately, one of the biggest factors holding it back as a do-it-all device was right there in the name: it was still a PlayStation, after all. The PSP had a D-pad and buttons, but the iPod had a click wheel. The iPod had an interface for everyone, but the PSP was for gamers first and foremost. Which was, to some degree, just fine — that’s why Sony ended up selling over 80 million of them. But it wasn’t a breakout multimedia gadget.

All of this seems quite obvious in hindsight, but I assure you it wasn’t at the time. Full credit goes to the few who called it in advance, like veteran game journalist Chris Kohler, because the PSP was getting rave reviews not just from the gaming industry but even from mainstream outlets like Time and CNN.

I thought the PSP would go on to define the future of portable entertainment. I’m not ashamed to say I got it wrong. Twenty years ago, holding it for the first time, the possibilities seemed limitless. How could I not believe?