Super Mario Odyssey is the purest form of Mario

Odyssey's strangely varied levels are key to why it is the quintessential 3D Mario game.

It’s January 2017. Nintendo is holding an event to give a first look at games for their daring new console, Switch, including a trailer for a new Mario game.

Mario games are landmark releases. Many are considered among the greatest games of all time. Mario is more than Nintendo’s mascot, he’s an icon for gaming itself. There is so much anticipation over just what Nintendo will do with Mario on their new console.

I can’t wait. Mario is my favorite character.

Then the trailer starts, and all I can think is: oh no.

That first Super Mario Odyssey trailer showed Mario running and jumping around a realistic (ish) cityscape, complete with traffic lights and New York-style taxis. There are even humans, real ones with normal body proportions, walking alongside Mario’s squat body and cartoonishly oversized head.

This is worse than the uncanny valley. This is Sonic the Hedgehog territory.

I’m not trying to re-ignite the console wars here, but tonal mismatches have always been Sonic’s domain. He’s the walking, talking, oddly large bipedal hedgehog running around realistic environments cities talking to normal humans (and, uh, kissing a human girl).

Mario, on the other hand, exists in a world that is itself a recognizable character. Christian Donlan observed that everything in most Mario games “seems made out of Mario-esque materials.”

“You know, the stones that make up the Princess' castle will be rounded and clean and smooth and noble,” Donlan wrote on Eurogamer. “The trees will be a bobbly delight.”

Super Mario Odyssey is not like that at all. Along with the New York-esque New Donk City, there’s also a dark, wooded forest and a crumbling, lightning-struck tower. The latter is inhabited by an enormous dragon; one rendered in the sort of muted colors and extreme detail that make the mythical beast look real. Mario, cartoony, colorful Mario, looks horribly out of place.

But this, strangely, is exactly why it worked. Super Mario Odyssey received massive critical and commercial acclaim. It is, as of this writing, the highest-rated game ever on OpenCritic. And to me, Odyssey is the purest expression of Mario in 3D — and those unusual environments are the key.

To understand why, we need to look at Super Mario 64, the first 3D game in the series and a milestone for the industry as a whole. Moving to 3D forced the designers to rethink everything, even down to the basics.

In 2D Mario games, the objective is, literally, straightforward: Mario faces right by default, and moving to the right takes you towards the goal.

Super Mario 64, though, featured an open 3D world where Mario could go in any direction. Seen from above, its stages were roughly square-shaped. When a game's level is shaped like a line, the goal is obvious: head for the opposite end. But where is the goal in a square level? How do you lead players towards an objective while also encouraging them to explore?

Make the level too open and players will get lost. But make the path too obvious and players won’t ever stray off it. What’s the point of creating a large and detailed map if players have no reason to visit every part of it?

The solution was to put multiple objectives inside a single level. It allows designers to repurpose parts of the level that go unused in one objective to house a different objective. Some were quite specific, like reuniting a penguin with her kids. But others broadly followed the same pattern across multiple levels, like defeating a powerful enemy or climbing to the highest point.

These common objectives play on our understanding of the grammar of games. If there’s an oversized enemy, a gamer instinctively knows that there will be a good reward for defeating it. If a line of hoops appear, a gamer's Spidey Sense tingles because they know what to do. The hoops were deliberately placed for you to go through them, all of them, without missing any. That’s just how games work.

Completing objectives in Super Mario 64 results in players receiving a Power Star. Collecting a certain number of these unlocks more levels and allows you to progress through the game. Super Mario 64 had 120 Power Stars in all, as did Super Mario Galaxy and Super Mario Sunshine (albeit called Shine Sprites in this one).

But Super Mario Odyssey shakes up the format with 880 Power Moons. It’s not because it’s a bigger game, it’s because it hands out Power Moons far more often than previous titles awarded Power Stars.

You still get Power Moons for big things like defeating bosses or climbing to the highest point of a level. But you also get them for smaller, more mundane things. One might be tucked away in a corner. More are found in boxes, down pipes, through a suspicious looking wall. Another is down a pathway that isn’t so much hidden as innocently lying slightly off the main path in plain sight; a little thread dangling on the edge of your eye line, tempting your curiosity to take hold.

Curiosity has always been part of the Mario series, right from the start. There’s always been an element of “what if” — what if I go down this pipe? What if I jump over the top of the screen?

Odyssey takes this a step further by building on that knowledge of the series. You know how far Mario can jump, and that jump looks just enough to make that gap — and on the other side is a Power Moon. You know that you’re supposed to go towards the right, so what happens if you turn left? Ah, there’s a Power Moon.

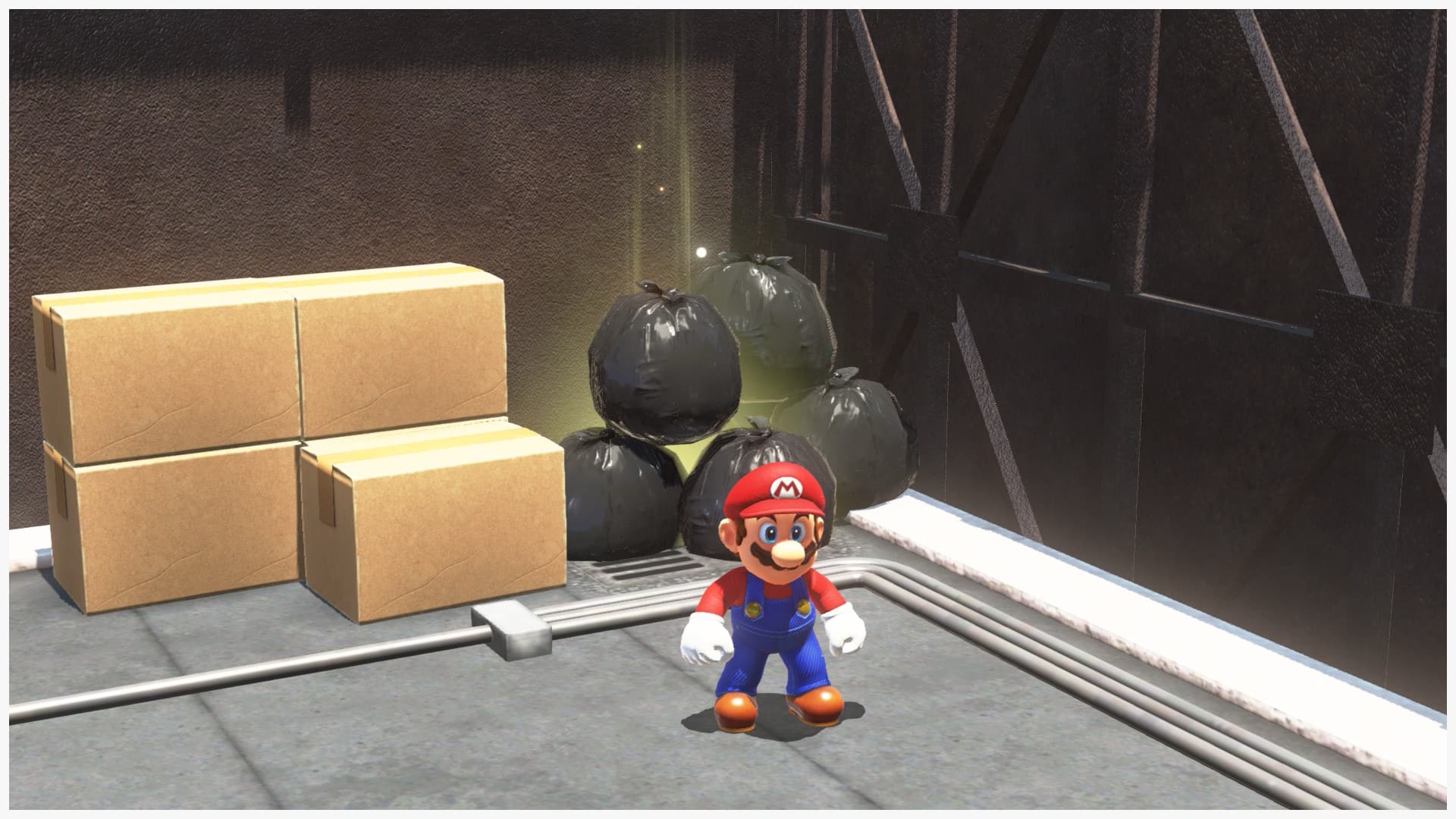

And this is where the seemingly incongruous levels play a part. If Odyssey used traditional Mario environments, the tells would be more obvious: you know what a classic breakable brick block looks like, or that a beanstalk leads to a secret area. But New Donk City doesn’t have magic beanstalks. It has back alleys filled with trash.

And yet, your instincts still kick in: there’s a Power Moon behind that pile of trash, right? (Yes, there is.) Odyssey’s levels are full of familiar patterns wrapped in unfamiliar visuals. It takes the same concepts and tropes and puts them in wildly different settings to the ones you’re used to. And whenever you follow your hunches in the right direction, it rewards you with a Power Moon.

Stripping away the traditional look of a Mario level allows this element to be the focus of the game. Without the classic visual cues, you have to work harder to recognize the patterns. The muted greys and realistic architecture of New Donk City may look like a deeply alien setting for the bright, cartoon-like world of Mario. But squint and you’ll realize that a seemingly unclimbable row of skyscrapers actually contains a row of ledges aligned in just the right way to form a path to the top. And you know that something good will be up there waiting for you.

Odyssey is not set in a Mario world, but it constantly forces you to look for opportunities to do Mario things. It dangles Power Moons as a reward for your curiosity, daring you to try to jump over that, to throw your hat over there, to stomp the ground here.

Super Mario Odyssey is the purest expression of a Mario game, because it rewards you for playing like Mario.