The Driver paradox

My one infallible rule about video games... and the one game that stands as an exception.

A quick announcement: Ravi 64 is now available on the social web! If you're on Mastodon or Threads, you can follow this site and receive all of my posts at @feed@ravi64.com

One of the core tenets that I have always believed about video games is this: if you start playing a game and it’s fun to simply move your character around, the game is going to be great.

Think of Super Mario 64’s opening in the garden outside Peach’s castle. Before you enter a level, before you even walk through the castle doors, the game begins in the castle grounds. There are trees, slopes and a big pond, but there isn’t anything specifically to do there.

And yet: think about how long you spent in this seemingly meaningless area, running and jumping, climbing trees, diving into water; not doing anything in particular, just playing. There’s no objectives, no enemies, no real challenge, but this area became a playground and a huge time sink.

Nintendo nailed the core feel of the game to a degree where it was fun just to perform the most basic action, moving. And this, in turn, makes building every other part of the game so much easier. You don’t have to push players to explore or experiment because they’re already enjoying doing that on their own. I firmly believe that this is the key ingredient that makes Super Mario 64 one of the greatest games of all time.

Okay, there are great games that don’t contain the same amount of joy in their controls. Red Dead Redemption 2, for instance, is a brilliant game, but mechanically it’s a slog. While it is fun to play Red Dead and exist in that world — to ride on horseback across the vast and beautiful land — that’s in spite of the sluggish, complex controls.

Controls aren’t the defining feature of a classic game, sure. But I’ve found that a game that makes basic movement fun is going to be great, every time...

...well, with one exception. Meet Driver, released in 1999 for the original PlayStation.

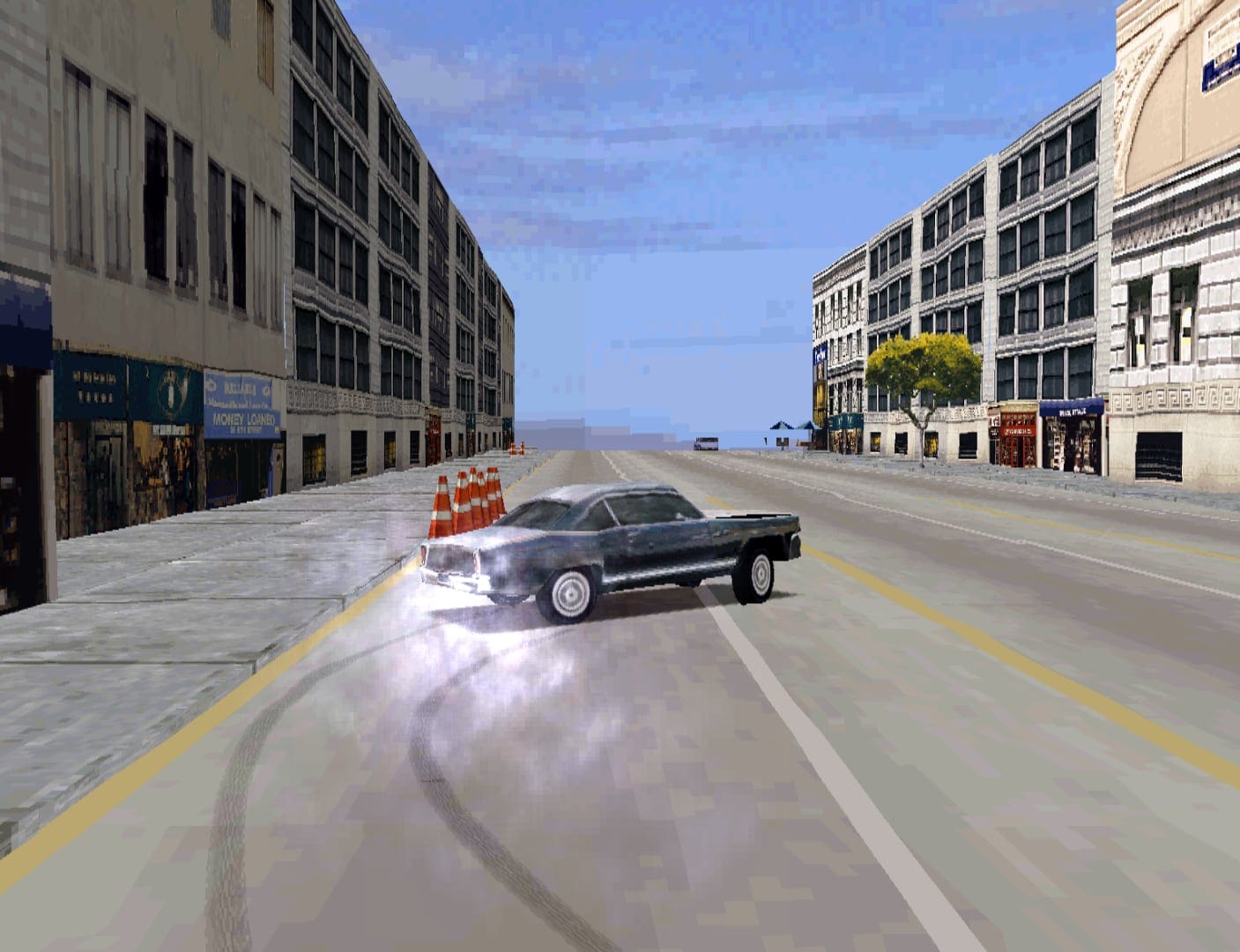

Driver is an action driving game based on 1960s and 70s car chase films like Bullitt and The French Connection. It was one of the first games to not just reference cinema, but try to replicate it. Chases take you through alleyways full of conveniently-placed boxes to smash into and glass panes to shatter. Turn sharp enough and you can dislodge your own hubcap, sending it rolling down the street.

It was glorious to play, because the core driving model felt so good. Developer Reflections nailed the balance between making the handling feel slippery enough that you could easily launch into drifts, but also grippy enough that you could control your slide. Ducking into an alleyway, dodging the debris left by the car in front really did feel like you were in a classic Hollywood car chase. It even had a film director mode to record gameplay into cinematic snippets, a remarkable technical achievement for the original PlayStation.

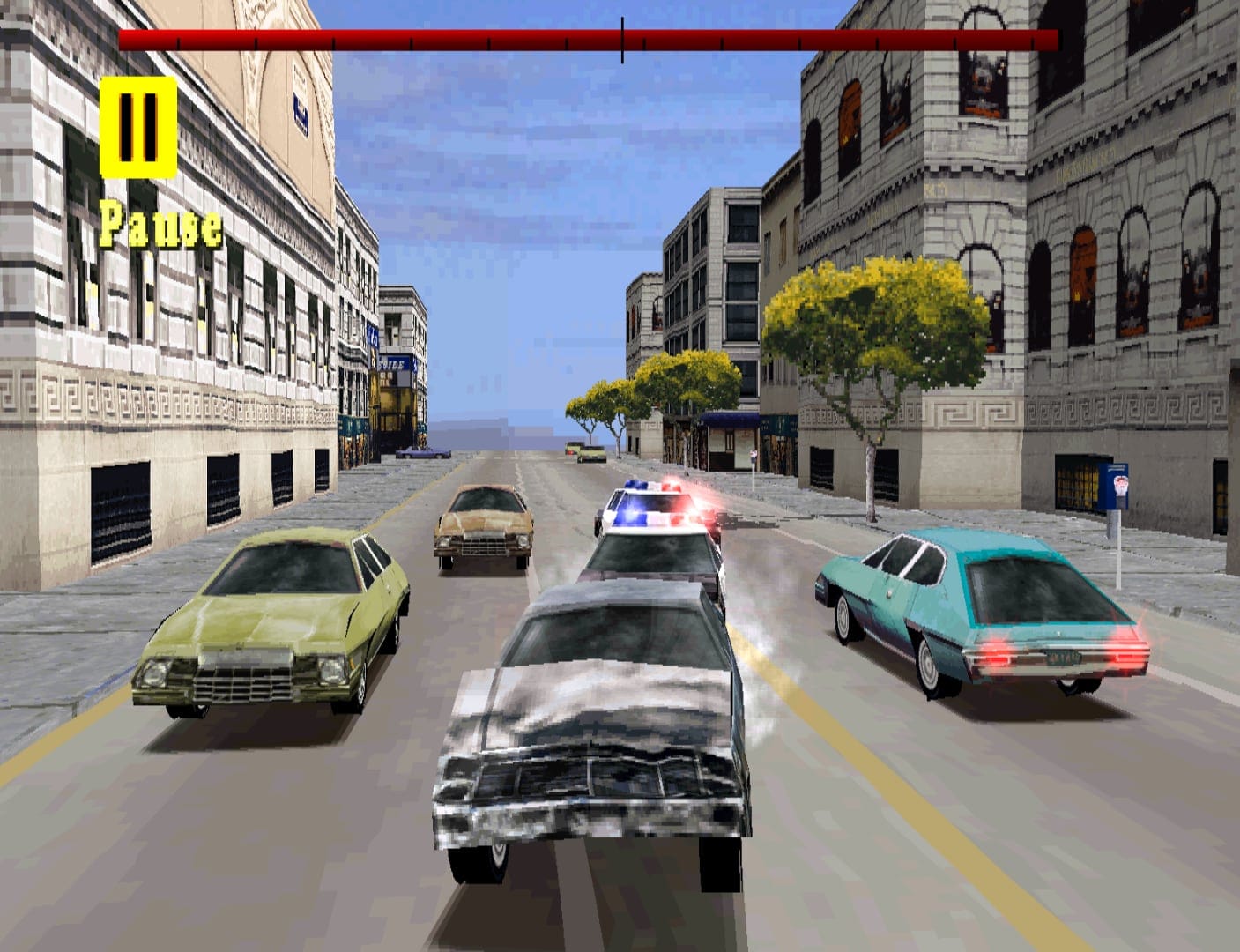

The thing is, while the core driving mechanics felt great, Reflections struggled to build on that base and create an actual video game out of it. They nailed the basic car chases, but they couldn’t figure out how to turn that into a proper video game campaign.

The solution they hit upon was to just increase the difficulty. Driver is a notoriously hard game: plenty of people couldn’t even get past the tutorial, including Sir Lewis Hamilton. In a game that makes smashing into stuff so much fun, later cities have strict requirements not to damage your car while driving along tight roads with barriers on either side. It wasn't challenging, it was stressful. It took the joy out of a game that was inherently fun.

I don’t think it’s any coincidence that, alongside the main story mode, the main menu allows you to also play five different chase minigames. Reflections found it easier to remix the core formula than to advance it, to keep giving you those same old car chases in slightly different contexts. And they were good fun to pick up and play, sure, but they lacked any depth.

To be fair to Reflections, Driver might have been a victim of the technical limitations of its era. It was a driving game with a huge 3D open world a whole generation before Grand Theft Auto III. That meant the world was simplistic and lacking in detail or other activities. You couldn’t even get out of the car, limiting the opportunities for gameplay variety.

So many games are able to take a simple core premise and craft a game around it. Nintendo has been doing it for ages, and continues to do so. Super Mario Odyssey director Kenta Motokura told me that, when they built the game, Mario’s moves came first. They focused on his feel, on the things that would be fun to do (like throw his hat), and then built the levels around that. They tuned the layout based not just on what moves and techniques would challenge the players, but the ones that they’d enjoy using, too.

Driver stands as a rare example of the opposite, a game with a core feel that is inherently fun but with no lasting depth. It is an exception, but one that proves the rule.