The stories you make and the stories you’re told

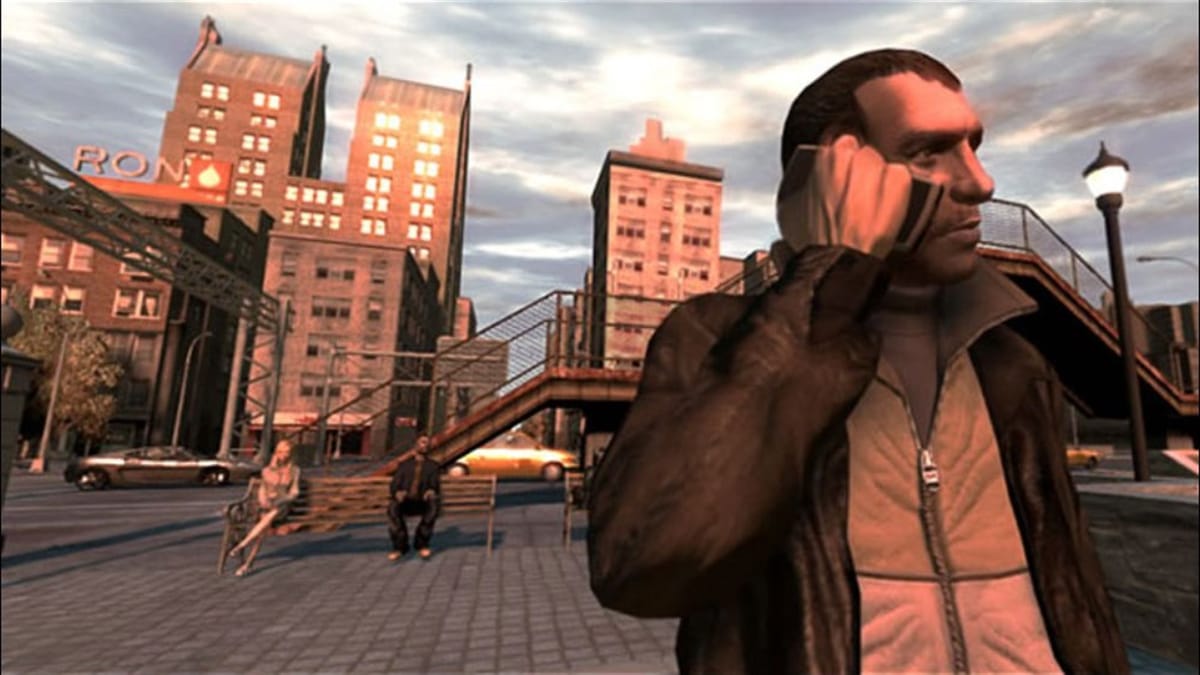

How GTA IV showcases the good and the bad of storytelling in video games.

A few hours into Grand Theft Auto IV, you’re hit with a big reveal.

A mob boss who you had been working for turns on you. And so you kill him. It feels like a big moment, the end of GTA IV’s first act. And in the immediate aftermath, you turn to your cousin and deliver a revelation: you didn’t just come to New York to see him. You didn’t just come here for the American Dream. Your prime motivation is to find a traitor from your past.

It feels like a big moment. It feels important and notable. It also falls flat, the start of a deeply unsatisfying plot line in a game filled with great storytelling, from a developer practically revered for their mastery of it.

In this case, the opening act provides two contrasting examples: how to do it right, and how not to.

You spend the early hours of the game inhabiting the life of your character, Niko Bellic, a former soldier who fought in the Balkans. Sold on the American Dream by your overly optimistic (and hopelessly misguided) cousin Roman, you’re surprised to find yourself in a roach-filled apartment helping out a failing taxi business, a far cry from the promised mansions and millions. To help out, Niko starts working for Russian mobster Vlad Glebov.

Vlad is, to be blunt, an asshole. He constantly insults Niko and Roman, demeaning and belittling them. And then he takes it a step further when he reveals that he coerced Roman’s girlfriend into having an affair. When Niko then vows to kill him, as a player, you’re fully on board with this. His barbs may have been aimed at Niko instead of you, and his affair is one that takes place inside a video game, but it matters because you’ve been along for the ride the whole time. You’ve seen how he treats Niko; you’ve heard how besotted Roman is with his girlfriend. You don’t need to tell me that Vlad is a bad guy, because you’ve shown it to me. It’s a great bit of storytelling.

After killing Vlad, Niko admits to Roman that he didn’t come just to see Roman; he’s chasing a traitor who betrayed his military unit, leading to their destruction. But Niko’s emotional admission falls flat, because it’s a case of telling instead of showing. You never see the unit’s destruction. You never know the comrades Niko lost. The traitor betrayed Niko: he didn’t betray the player.

The concept of ludonarrative dissonance — the conflict between the actions of a player and a game’s story — is not a new one. It’s an especially big problem in open world games, where the freedom granted to players can be at odds with certain parts of the narrative. In cinematic story sequences, your character might present themselves as an honorable person; a criminal, yes, but one with morals. And then after that sequence ends, players can go off and gun down scores of civilians with that same character. A game’s story should be reinforced by its gameplay; when there’s a gap between the two, it feels strange and takes you right out of the world.

Another prime example comes from near the end of GTA IV. (Sorry, spoilers for a game that’s 15 years old.) Niko attends Roman’s wedding with a date, Kate, sister of a criminal associate. An old rival crashes the wedding and guns down Kate. Niko, furious over the death of his beloved girlfriend, swears revenge, setting up an emotional finale.

There’s just one problem: in my game, Kate was never Niko’s girlfriend.

GTA IV forces you to go out with Kate once as part of the story; then she becomes just one of five women Niko can call for a date. After that first time, I never called her or any of the others back. (GTA IV’s social mechanics were… not super fun.) I exercised my freedom of choice as a player, not knowing that the game had plans for Kate. And so rather than feeling empathy for Niko at a major moment in the story, all I felt was confusion: who is she again? Why is he so upset?

Rockstar normally doesn’t get this sort of thing wrong. The two Red Dead Redemption games, in particular, represent some of the best storytelling in any game, let alone open world titles. More than anything, they embody the ethos of show, don’t tell.

GTA IV wants Kate to be part of Niko’s story. But she doesn’t mean anything to me, because as a player, she wasn’t part of my story. The stories you make for yourself will always be more powerful than the stories you’re told.